The Best Exotic Portugal Hotel: Canijo Examines Motherhood as Misanthropy in Masterful Familial Miasma

The women handling the specialty boutique hotel in Joao Canijo’s Mal Viver (Bad Living) have inadvertently created their own inescapable prison. Like the cursed souls inhabiting the metaphorical hell of The Eagles’ “Hotel California, which eerily asserted “You can check out any time you like/But you can never leave,” three generations of women careen towards self-destructive implosion, predatory insects tangled in a web of their own making.

The women handling the specialty boutique hotel in Joao Canijo’s Mal Viver (Bad Living) have inadvertently created their own inescapable prison. Like the cursed souls inhabiting the metaphorical hell of The Eagles’ “Hotel California, which eerily asserted “You can check out any time you like/But you can never leave,” three generations of women careen towards self-destructive implosion, predatory insects tangled in a web of their own making.

For fans of Canijo, who often operates in the same vein as Mike Leigh in the lengthy collaborations of his scenarios with the same coterie of performers over the past several decades, it’s a return to the acidity of his best traveled title, 2011’s Blood of My Blood, another agonizing familial epic which is more sensationally perverse. In an interesting creative move, Canijo has also filmed a mirror film, Living Bad (read review), a partial shot-reverse-shot featuring a trio of interlocking stories involving the hotel’s equally unhappy guests, oblivious to the intergenerational pain of their hosts.

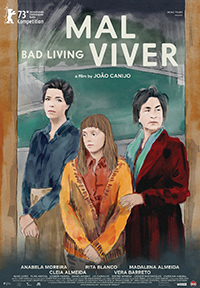

Four women single handedly run a family owned hotel by the Portuguese northern shore, each of them playing multiple roles to keep it running. Sara (Rita Blanco) is technically in charge, assisted by her two daughters, Raquel (Cleia Almeida) and Piedade (Anabela Moreira). Along with chef Angela (Vera Barreto), they cook, clean, and provide front desk services when they aren’t bickering. They’re suddenly joined by Piedade’s estranged daughter Salome (Madalena Almeida), whose father died only four days prior. Piedade did not attend his funeral, and seems more connected to her dog than her daughter. Instantly, old wounds are torn open, and the emotionally impervious Piedade finds herself confronting simmering resentments she has for Sara. Meanwhile, a trio of guests show up to engage in their own private miseries, though they’re unwitting spectators to an endless cycle of familial animosity which seems to feed into their own specific ennui.

Swedish playwright August Strindberg is an obvious reference point for Canijo’s sister films, the inherent misogyny of textual influences exacted by and almost inherently between the vast intersections of women despondently wasting away in the unhappiest hotel since The Overlook. But Bad Living has a contained, gleefully bitchy Tennessee Williams vibe, this time around with an almost equal spread of despair amongst the ensemble. Canijo’s celebrated mainstay, Rita Blanco, might be the narrative’s root of evil as Sara, the gloomy matriarch who has only proven to her daughters how conditional a mother’s love can actually be. Absence makes the heart grow fonder, and granddaughter Salome is the only object of her affection. Salome’s return home following the recent death of her father is the dramatic environmental shudder initiating the storm clouds over both films, the interchangeable sense of misery infecting everyone unlucky enough to spend time in the hotel.

Sara’s manipulations are readily apparent to an objective viewer, but her constant gaslighting of her own children, specifically Piedade, has become a tenet of their interactions. Lording over their dwindling operation (she’s a fan of Clarice Lispector, and seems to approach her daughters like the dying cockroach in The Passion According to G.H.), she warns Piedade she “should be scared when I die,” threatening to sell the hotel, on the verge of falling into dilapidation.

Anabela Moreira gleans the most empathy, constantly lurking in the corridors to hear her desolate family speak ill of her. “It’s like there’s a void inside her and you have to keep filling it,” Sara advises Salome, even though it’s a sentiment which describes the rest of them just as well. It’s no wonder Piedade’s greatest love is the newest edition of her lap dog, Alma, a creature whose absence causes the only great alarm in her life. “I don’t know how to love anybody,” she eventually explains, perhaps the only logically distilled, authentically true statement anyone utters. With these string of mother-daughters feeding off one another’s emptiness, Bad Living offers up a pair of peripheral players, including Piedade’s more vivacious sister, Raquel, a bisexual who causes her own ripples of dismay when she sleeps with a married guest, alerting us to a codependent relationship she’s developed with the hotel head chef, Angela. Apparently, Angela has only stuck with this sinking ship for her love of the family, but a secretive relationship with Raquel is more likely the tie that binds.

Much like the split screen Canijo employed in Blood of My Blood, he examines the spatial dynamics of these women in the hotel by returning to various long shots showing a cross section of their movements. Despite the logistical possibilities, they constantly seem to be on top of one another, and privacy seems to be nonexistent mostly thanks to their lack of boundaries, eroded by years of self-created imprisonment. Snippets of the guests and their various predicaments spill over into the shared public spaces, such as an agonizing dinner sequence, where Raquel and Piedade prattle on about the food and the paired wine to their oblivious clients, not unlike the socially cursed Shelley Duvall in Altman’s 3 Women (1977).

As Bad Living veers into inevitable tragedy, we’re left pondering, “Who’s the biggest problem?” There’s never a moment where it doesn’t seem like all these women likely want to (or need to) run away screaming from one another, a sentiment the audience will likely share. But this is inherently the essence of Bad Living, concerning a handful of humans making decisions which actively poison them slowly, until someone invariably can’t take it any more.

Reviewed on February 22nd at the 2023 Berlin International Film Festival – Competition section. 127 mins.

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆