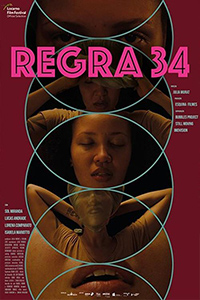

Cam and See: Murat Explores Pleasure Principles in Provocative Portrait

“She does it for the thrill, even if it kills,” might be a good tagline for the sobering but subversive Regra 34 (Rule 34), the third film from Brazil’s Júlia Murat, walking down a dark road of titillation, impulse control and the oft repressed parallels between sex and death. The film, which plays like the even kinkier, contemporary version of something like Belle de Jour (1967), really is about sex death in its protagonist’s fascination and eventual obsession with autoerotic asphyxiation, a compulsion both countered and enhanced by her daytime proclivities as a student of criminal law defending the rights of women who often have no control over their bodies. Add to this an overshadowing awareness of racial inequity, and Murat has formulated a potent recipe of dangerous intersections in a film titled for a maxim asserting there is a pornographic representation of any conceivable theme or object.

“She does it for the thrill, even if it kills,” might be a good tagline for the sobering but subversive Regra 34 (Rule 34), the third film from Brazil’s Júlia Murat, walking down a dark road of titillation, impulse control and the oft repressed parallels between sex and death. The film, which plays like the even kinkier, contemporary version of something like Belle de Jour (1967), really is about sex death in its protagonist’s fascination and eventual obsession with autoerotic asphyxiation, a compulsion both countered and enhanced by her daytime proclivities as a student of criminal law defending the rights of women who often have no control over their bodies. Add to this an overshadowing awareness of racial inequity, and Murat has formulated a potent recipe of dangerous intersections in a film titled for a maxim asserting there is a pornographic representation of any conceivable theme or object.

More sinister than it is alarming (and a further exploration of sexuality than in her previous title, 2017’s Pendular), it’s a fascinating portrait of desire flourishing within the specific confines of a personal vacuum built on projection, leading to the real confrontation when the ethereal anonymity of online sex becomes corporeal. Murat constructs one woman’s private insurgency on the battleground of her own body, generating a lot of questions along the way. If the personal is political and sexuality is personal, where does pleasure end and academe begin? Can pleasure be political? And if it can, is this the point where we lose ourselves and emotion becomes apathy?

Simone (Sol Miranda), a twenty-three year old Black woman studying to be a public defender in Rio de Janeiro, spends her evenings sexually pleasuring herself online at a porn site called Chaturbate. As she increasingly becomes aware of the futility of her country’s laws to protect women’s rights, witnessing first hand preventable violence against a woman she’s worked with as a legal consultant, Simone redirects her anger into her private activities. Initially, there’s productive rationalization, aided by her self-defense classes she attends with another student, Lucia (Lorena Comparato), but her resistance to compartmentalizing the detached, impractical lectures with the reality of the racism and misogyny flourishing around her leads to increasingly risky behavior. Whereas the legal world is strictly defined, there’s a remarkable fluidity in her sexual partners, engaging in three-way sex with Lucia and another classmate, Coyote (Lucas Andrade). But her friend and confidante Nat (Isabela Mariotto), who is invested in her own BDSM ventures, introduces Simone to a video containing a more graphic sexual interaction. Shortly after, on the chat site, Simone’s fans demand she perform autoerotic asphyxiation on cam…and one thing leads to another.

Such unabashed and unexaggerated sexual pleasure makes Rule 34 feel like the natural progression of the French New Wave, striking a vein of fluidity and hedonism which lulls us into a sense of security about Simone’s maturity. Her early sequences on cam, and eventual sexual interactions with two of her fellow students are playful, liberating, and sweet. But Simone, who is compellingly portrayed by Sol Miranda (making her debut) as an intelligent and adventurous woman, gets caught up in her own existential crisis. Using her own body as a statement of agency, her initial dalliance arguably evolves into a rebellion against the misery she’s confronted with in her pursuit of becoming part of the judicial system.

Desiring to be a progressive helpmate, she begins to realize her limited capacity in the necessary but archaic legal system. Her exuberance in asserting such triumphant control, however, invites a chaos which causes the loss of her control. Absorbing social violence by embracing it as a tool for pleasure eventually erodes her stability, and not unlike Isabelle Huppert in Elle (2016), must confront the reality of a situation which suggests the probability of harm rather than a semblance of equity.

The juxtaposition between the realms Simone is straddling is not presented as a stark contrast, at least visually, the only difference between the procedural courtroom melodrama and the sensual promises of the night being the inclusion of clothes, at least as lensed by Leo Bittencourt to perhaps suggest everything’s subject to ingrained mores.

False narratives, bolstered by time and unchallenged rhetoric are pervasive, as evidenced by an exchange where Simone confirms a commonly assigned quote to Frida Kahlo was never actually uttered by the artist. Ultimately, Simone’s sexual liberation and her refusal to accept the rules and regulations applied to both her daytime pursuits or her nighttime pleasures, is still, unfortunately, a simple but radical subversion of the patriarchy. But Murat includes the unease accompanying any vigilante’s odyssey by not avoiding the real possibility of danger and harm for those who aren’t supported by a community. Initially, Simone’s friend-lovers provide a sort of support or a safe space, but there’s an inherent thrill in exploring the unknown, thrills which yield addictive pleasures or irreversible consequences. These are the energies clashing in the form of Simone in Rule 34, and perhaps one’s own rigidity will inform their reaction to the point of no return in which Murat deposits her. And if you don’t like such troubling ambiguity, don’t blame it on Murat – blame it on Rio.

Reviewed on August 13th – Concorso internazionale. 100 Mins.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆