Baby Machines: Delpero Designs Tapestry of Women’s Miseries During WWII Italy

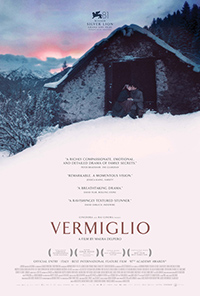

Despite the associations suggested by its title, Maura Delpero’s sophomore film Vermiglio is a rather cold, calculating, rigid portrait of an isolated mountain village in Italy at the tail end of WWII. While the title is the name of the small community, made up almost entirely of women, children, and the aging men who were too old for military service, in English it means ‘vermillion,’ a scarlet hue used to describe lips as well as a toxic pigment produced by a chemical reaction between mercury and sulfide (not to mention its representation as a bird symbol in Chinese mythology). Passion, energy, and excitement are automatically synonymous, and these are the opposite elements of a blue-tinted world created by Delpero. Focusing on an integral family in the community, Delpero leads us through essentially a year in their life, which straddles the official end of the war and transformational experiences which quietly devastate them.

Despite the associations suggested by its title, Maura Delpero’s sophomore film Vermiglio is a rather cold, calculating, rigid portrait of an isolated mountain village in Italy at the tail end of WWII. While the title is the name of the small community, made up almost entirely of women, children, and the aging men who were too old for military service, in English it means ‘vermillion,’ a scarlet hue used to describe lips as well as a toxic pigment produced by a chemical reaction between mercury and sulfide (not to mention its representation as a bird symbol in Chinese mythology). Passion, energy, and excitement are automatically synonymous, and these are the opposite elements of a blue-tinted world created by Delpero. Focusing on an integral family in the community, Delpero leads us through essentially a year in their life, which straddles the official end of the war and transformational experiences which quietly devastate them.

It’s 1944 in a remote village nestled quietly in the Italian Alps. A Sicilian foreigner, Pietro (Giuseppe De Domenico) has made his way to the community with one of their own, also a deserting soldier whose experiences have left them both altered. The community agrees to let him stay, and his attraction to a beautiful young woman named Lucia (Martina Scrinzi) is reciprocated. She’s the eldest daughter of the village school teacher, Caesar (Tommaso Ragno), an aging patriarch who looks as if he’s old enough to be the grandfather of his young brood. His wife Adele (Roberta Rovelli) has recently birthed their ninth child and is pregnant with another. But their latest infant is sickly, and not destined to reside long in their world. Splintering family conflicts unfold, including with his eldest son Dino (Patrick Gardner), who treats his stern father with contempt. Dino also shares a flirtation with their neighbor, Virginia (Carlotta Gamba), who likes to wear makeup and smoke cigarettes in the barn, fascinating one of his younger, more enterprising sisters. As the war ends, Pietro returns to Sicily temporarily, but as time goes on and no word is received, it soon becomes apparent something is terribly wrong.

Delpero, whose 2019 debut Maternal also dealt with an isolated group of women whose dynamics are uprooted by the sudden appearance of someone new, unfolds the narrative with solemn visuals, first opening on a frozen, wintry world which will soon thaw. We piece together more about the characters, who slowly come into focus, through the visual information we receive rather than explicit dialogue, which arrives in stops and spurts, usually amongst characters, particularly children, trying to reassure or understand what’s going on. The crisp beauty of its frames are courtesy of DP Mikhail Krichman, responsible for the ominous glaze of Andrey Zvyagintsev’s filmography, perhaps most reminiscent of 2011’s Elena, which is also about a desperate woman struggling to remain intact.

What emerges beyond the characters are the excruciatingly limited options for women, basically expected to be baby making machines to ensure a steady supply of able bodied community members to engage with the labor of surviving in their environment. The war is a distant terror, but their eagerness to take Pietro in and keep his whereabouts secret from whomever may come knocking also suggests a cult-like realization of fresh blood being needed. Especially if new members are of the male persuasion. Pietro is mostly a silent figure, and the villagers assume he’s shellshocked. The romance shared with Lucia is told through distant glances, conveyed via clandestine notes, the evidence of their lovemaking evident by Lucia’s pregnancy, resulting in their marriage.

It’s only here where we finally begin getting a sense of Caesar’s omnipotent designs for the members of his family, as if the winter thaw also loosened tongues. Lucia’s been hemmed up by a foreigner, and eldest son Dino is a disrespectful disappointment to good old dad. With Adele birthing her tenth child, the time seems to have come to cement the future of the others. We focus a bit on Ada (Rachele Potrich), who is secretive and earnestly pious. Having recently discovered masturbation, her awareness of its sinfulness has her engaged in a whirlwind of self-inflicted expiation, which includes eating chicken feces in order to obtain atonement for her wickedness. Her father compliments her on her efforts, but at the end of this current curriculum, Ada is informed her schooling will now end as she didn’t prove herself worthy of receiving more knowledge. Instead, he favors the precocious Flavia (Anna Thaler), who may not have attention for details but is whip smart. She will be the only member of the family to receive a continuing education, for they cannot afford to utilize the others for anything but labor.

If this doesn’t seem depressing on its own, a bombshell blows all these quiet miseries to smithereens when a newspaper confirms why Pietro never returns from Sicily. Having already been married with children, he’s murdered to protect the honor of his first wife from his bigotry, leaving Lucia reeling. Cesar has conditioned his wife and daughters too well, for she immediately sets about punishing herself. Her baby is born, her world now so extremely limited one would expect Delpero to take pity on her and stage a suicide. But surprisingly, there’s some hope. There are options, though minimal, to resist the Sisyphean drudgery they’ve been led to believe is the only way.

While it takes a bit for the orientation of these characters to align, one’s patience is well earned for a compelling portrait of resilience and resistance. There’s an earthy, rustic tangibility to some of these images, conjuring the textures and smells associated with rituals and locations. Taking place across a cycle of seasons, Delpero fittingly utilizes Vivaldi to underscore the roiling sumptuousness always dwelling beneath the surface of human experience, and though it’s simple, a final absence speaks more volumes than any words could.

Reviewed on September 2nd at the 2024 Venice Film Festival (81st edition) – In Competition section. 119 Minutes.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆