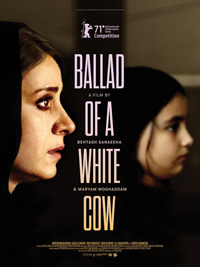

Kismet Kisses: Moghaddam & Sanaeeha Mine Intimate Vengeance in Rich Melodrama

The opening moments of Ballad of a White Cow evokes a quote from Al-Baqarah or The Surah of the Cow, the second and longest chapter of the Quran. Within this surah, more than one cow is featured, but the reference regards the slaughter of a cow as a message delivered by Allah to the Israelites through Moses, an action which will reveal who murdered a slain man. Caught in the middle, of course, is a poor, innocent cow.

The opening moments of Ballad of a White Cow evokes a quote from Al-Baqarah or The Surah of the Cow, the second and longest chapter of the Quran. Within this surah, more than one cow is featured, but the reference regards the slaughter of a cow as a message delivered by Allah to the Israelites through Moses, an action which will reveal who murdered a slain man. Caught in the middle, of course, is a poor, innocent cow.

While this is a rudimentary, and superficial starting point for examining the happenings of this tale of karmic vengeance, it’s the first narrative feature from directors Maryam Moghadam and Behtash Sanaeeha, who previously delivered the 2018 documentary The Invincible Diplomacy of Mr. Naderi, and heralds the pair as a new, eloquent creative force in Iranian cinema. Moghadam, who also stars, is equally transfixing on screen, and previously co-wrote and starred in Sanaeeha’s debut Risk of Acid Rain (2015), though she might be best known for appearing in Closed Curtain (2013) by Jafar Panahi and Kambuzia Partovis.

Mina’s (Moghadam) life has been turned inside out following the arrest and eventual execution of her husband, Babak, convicted of murdering a man. She’s left to fend for herself while providing care for her young child, Bita (Avin Poor Raoufi), who is deaf (credited to a difficult pregnancy). Applying for welfare does not guarantee she’ll receive assistance, and she depends on the kindness of her landlord’s wife to get by. Suddenly, she’s summoned, along with her brother-in-law (Pouria Rahimi Sam), by officials who confirm the real murderer has confessed, and Babak was executed in vain. A curt apology reveals there will be compensation, something Babak’s father plans on taking for himself by accusing Mina of being an unfit mother. As this drama begins to unspool, a kind savior named Reza (Alireza Sani Far) shows up on her doorstep stating he is an old friend of Babak’s and has returned to repay a debt. Mina is thankful for the consideration, but a strange man showing up at her home causes the landlord to evict her for indecency. But Reza gifts her a swank property at a bargain rental price. Soon, Mina becomes embroiled in Reza’s life, who has a troubled adult son, never guessing the true nature of the tie binding them together.

Essentially, the three main characters in White Cow resemble facets of the ‘see, hear, speak no evil’ adage, as a woman silenced, a judge blinded by his occupation, and a child not allowed to hear the truth. The narrative opens upon a white cow in the center of the Ka’ba in the Great Mosque at Mecca, seemingly ready for sacrifice. Another key theme is classical Iranian cinema, and Bita is named after a character played by famed actress Googoosh, whose career was ended, like many, by the Iranian Revolution. But Moghadam and Sanaeeha are also arguably paying homage to the classic 1969 title The Cow from Dariush Mehrjui, although it’s a title utilizing metaphors dictated by the actual death of a bovine creature.

Like many narratives contemplating the role of women in modern day Iran, Ballad of a White Cow is a frustrating exercise, as Mina is primed for victimization, even when the state admits its folly in executing her husband. Property becomes the sacrifice here, as Reza’s gift of his home to Mina eventually reveals, like the cow in the surah, the identity of Babak’s executioner (well, a representative of the perpetrators, let’s say).

Moghadam gives a quiet, empathetic performance and Amin Jafari’s cinematography drinks in her wide-eyed, shell-shocked expression, recalling the energy and presence of Lorraine Bracco. “God’s retaliation is the essence of our lives,” has been the reality of these characters, and ironically, Reza’s empathy ultimately tips the karmic trail against him. If Moghadam and Sanaeeha deliver a cold justice conjured by lessons in the Quran, Mina’s fate is a jagged edge sword which niftily defies Babak’s money hungry relatives, and thus a sticking point from the Book of Mark in the Bible referring to those “who devour widows’ houses” remains a twin sentiment in this menacing tale which suggests restorative powers of justice exist for those pushed beyond a breaking point.

Reviewed on March 4th at the 2021 (virtual) Berlin International Film Festival – Main Competition. 105 Mins.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆