The Day the Clown Cried: Phillips Tries to Provoke the Herd in Adult Comic Book Origin Story

As another cinematic iteration of the eponymous Joker encouraged in a previous film, “introduce a little anarchy,” which is what it seems Todd Phillips has set out to accomplish in his dark-hearted, R-rated origin story of the comic-book villain. Phillips, who the Golden Lion at the 2019 Venice Film Festival, is perhaps the unlikeliest of sources for both this tone and material seeing as his previous studio efforts consisted of The Hangover trilogy, Starsky & Hutch (2004), Due Date (2009) and War Dogs (2016). As we’ve come to learn and normalize, mainstream aficionados of any and all Hollywood super hero movies resoundingly reject any kind of poetic license taken with any reboots, sequels, franchises, etc., any deviation of which sparks an immediate backlash and are behaviors which have come to be associated with the incel subculture—coincidentally, this has been one of the troubled readings of Phillips’ film, which attempts to provide an empathetic portrait of a psychopath cultivated and groomed to be a monster by troubling social realities.

As another cinematic iteration of the eponymous Joker encouraged in a previous film, “introduce a little anarchy,” which is what it seems Todd Phillips has set out to accomplish in his dark-hearted, R-rated origin story of the comic-book villain. Phillips, who the Golden Lion at the 2019 Venice Film Festival, is perhaps the unlikeliest of sources for both this tone and material seeing as his previous studio efforts consisted of The Hangover trilogy, Starsky & Hutch (2004), Due Date (2009) and War Dogs (2016). As we’ve come to learn and normalize, mainstream aficionados of any and all Hollywood super hero movies resoundingly reject any kind of poetic license taken with any reboots, sequels, franchises, etc., any deviation of which sparks an immediate backlash and are behaviors which have come to be associated with the incel subculture—coincidentally, this has been one of the troubled readings of Phillips’ film, which attempts to provide an empathetic portrait of a psychopath cultivated and groomed to be a monster by troubling social realities.

Seemingly less concerned with how white privilege plays into this particular character’s descent into madness and violence, Phillips and scribe Scott Silver (The Fighter, 2010) highlight how classism, socioeconomic disenfranchisement, political corruption, the absence of gun control, and lack of medical care access contribute to the making of our white monsters in a way which is sometimes chilling, sometimes silly, often provocative and denounced as “dangerous” in some circles. If Scorsese’s 1976 classic Taxi Driver (a film which would have a hard time being made today unless it was disguised in popular frippery such as this) is a classier comparison for what Phillips concocts, what we have here is, without a doubt, a success thanks to an uncomfortable, disturbing portrait of a social outcast by Joaquin Phoenix.

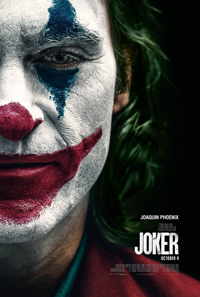

Designed as a standalone origin story of Batman’s infamous arch nemesis, previously portrayed by Jack Nicholson in Tim Burton’s Batman (1989) and Heath Ledger in Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight (2008), which won him a posthumous Best Supporting Actor Academy Award, Phillips and writer Scott Silver’s offering has been packaged as a “game changer.” However, its novelty is really a return to the grit we once saw filmmakers allowed to leverage in mainstream studio offerings, a tradition which slowly died out through the 1980s and 1990s, when rated R films became a box office burden for a need to wrangle the adolescent population and censor themes and realities teens were otherwise ingesting elsewhere. And thus, Joker is really more of a slight taste of shock and awe, supposedly daring in its perverse insistence we take a journey with a psychopath produced by capitalism and systemic racism. Had Arthur Fleck been a person of color, would his descent have yielded the same end result? There’s a nagging thread never pulled at in Phillips’ attempt at anarchy, which seduces us into a Death Wish paradigm, where a voiceless population taps into and helps empower the symbolic leader it needs for its movement.

While standalone, Joker feeds us nuggets uniting us with Burton’s childhood flashbacks of Batman, which doesn’t exactly help its argument as a trailblazing interloper one would hope. We learn the mentally ill Arthur Fleck is suffering from a condition where hysterical laughter becomes an autonomic nervous tic. His frail mother (Frances Conroy), whom he lives with and cares for, writes to the soon-to-be-campaigning-mayor Thomas Wayne (Bret Cullen) to save them from poverty, as she was once his employee. This leads to a subplot providing an additional dramatic catalyst, set to the background of Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936). Phoenix’s physicality is jarring, whether lounging in his emaciated frame or his jolting bolts through city streets, like a robot trying to break free of his body. A kind neighbor (Zazie Beetz) unwittingly shares a kind moment—however, Phillips doesn’t pursue the anxiety produced by this strand to conclusions one might predict. Instead, more questions are posed than answered, but the relatively simple narrative is this – a mentally unwell man finds himself fired thanks to a confluence of instances, watches himself be humiliated on television after a failed attempt at stand-up comedy (his dream) on the Murray Franklin (Robert De Niro) show, styled after a Merv Griffin or Johnny Carson personality, an instance which eventually creates his newfound persona as Joker. Somewhere in the mix there’s a triple homicide of some white Wayne employees which starts a media frenzy and generates a series of growing protests by the city’s lower classes.

Phillips’ early 80s Gotham is a topsy-turvy world, clearly modeled after New York City (lensed expressively by Lawrence Sher) of the same period, the mounting class tensions between the haves and have-nots reflected in the ominous garbage strike and the presence of mutated super rats roaming the filth ridden streets. But like the cursed pendulum that is mankind’s social progression, we’re still operating on the six inches forward five inches back course of action, which allows for this parallel period universe to feel eerily similar to our own, a world where homelessness has spiraled perilously out of control, civil liberties are being eroded, immigrants are being put in concentration camps, mass shootings are a weekly reality, and a faux-religious, nationalist zealot grooms what was once the symbolic haven for freedom and opportunity into a chaos machine in which hate speak has become insidiously normalized through euphemistic policies benefitting the wealthiest members of the population. And that’s to say, while Phillips’ angry snarl of a movie triggers reminiscence on all these fronts, it’s neither wise enough nor articulate enough to properly deal with anything beyond its commanding performance from Phoenix.

Presented neither as an anti-hero nor as a condonement for violence and villainy, what Joker does surprisingly well is showcase how easy it is to fall through the cracks but also the importance of practicing kindness towards one another. Joker opens with Phoenix dressed as a clown, taunted and beaten by a group of adolescents who steal the ‘Everything Must Go’ sign he’s wielding (an appropriate enough sign for the film’s sentiments for the selfish, lost souls who proliferate both on the streets of Gotham and those hiding in its ivory towers). Part of the film’s strength resides in its ambiguity, for Arthur Fleck, is, if anything, an untrustworthy narrator (the film gracelessly has to hit us over the head with what’s going with the Zazie Beetz character, however).

Some narrative coincidences lend a slight sense of contrivance, but the exaggeration of Phoenix is often balanced by mannered character performances from Brian Tyree Henry, Shea Wigham and Bill Camp. Frances Conroy, (used much more effectively here than in 2004’s Cat Woman) helps with establishing sympathy for Arthur. His complete assimilation into his new depraved persona is marked by Gary Glitter’s iconic pop song “Rock and Roll, Pt. 2,” a subversive nod to our ability to pick and choose our zeitgeist alums despite the problematic behaviors of the artists.

Bottom line is, Joker attests to a return to the human component necessary in these endless comic book dalliances (or as Alejandro G. Inarritu infamously referred to them, “cultural genocide”). If too much candy rots the teeth, then these sweet-nothings of Hollywood, which are often empty-headed blips of escapism, have allowed for the routine collective dismissal of anything which remotely challenges mainstream concepts of taste, form or expression. Maybe if we weren’t so obsessed with escaping from reality we could reestablish the empathy required to sustain civilization by dealing examining not just how social policies but our own individual behaviors assists in creation of psychopaths and sociopaths we so easily condemn, whose portrayals are ‘dangerous’ but not the conditions and policies which allow them to flourish.

Again, it’s not so much Phillips has made a brilliant film of our age, but the conversations surrounding it certainly reveal how a film community, of both audiences and critics, who are increasingly unable to properly weigh the importance of the matters or platforms on which they speak. Joker is not an exercise interested in exemplifying ethics, but the fact of it hitting too close to home for the audiences it was destined to entertain and appeal to is also not a detriment to its existence.

Reviewed on September 10th at the 2019 Toronto International Film Festival – Gala Presentations Program. 122 Mins.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆