The Town That Dreaded Showdown: Bouchareb Returns to New Mexican Landscape with Mixed Results

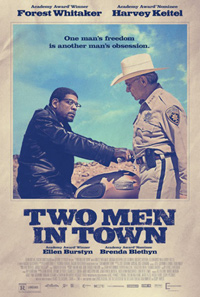

French director Rachid Bouchareb’s long celebrated filmography has garnered two of his titles Academy Award nominations for Best Foreign Language Film (Dust of Life; Days of Glory), along with a host of other accolades for a body of work that often revolves around either Algerian experiences in France (modern and period), or explorations of race and/or gender within unique narratives. A long-time producer of Bruno Dumont’s work, Bouchareb has been pursuing a variety of international productions. His latest, Two Men in Town, is a morality exercise that happens to take place in roughly the same US locale as his last effort, 2012’s Just Like a Woman. Despite a notable cast and several rather arresting performances, the end result never elevates beyond a standard dramatic exercise that ends in more or less the same place as it begins—a wide open expanse of dry, empty space.

French director Rachid Bouchareb’s long celebrated filmography has garnered two of his titles Academy Award nominations for Best Foreign Language Film (Dust of Life; Days of Glory), along with a host of other accolades for a body of work that often revolves around either Algerian experiences in France (modern and period), or explorations of race and/or gender within unique narratives. A long-time producer of Bruno Dumont’s work, Bouchareb has been pursuing a variety of international productions. His latest, Two Men in Town, is a morality exercise that happens to take place in roughly the same US locale as his last effort, 2012’s Just Like a Woman. Despite a notable cast and several rather arresting performances, the end result never elevates beyond a standard dramatic exercise that ends in more or less the same place as it begins—a wide open expanse of dry, empty space.

After serving eighteen years of his twenty-one year prison sentence for killing a deputy, William Garnett (Forest Whitaker) is granted parole. Renouncing his violent past as a criminal and embracing his new existence as a Muslim, Garnett is deposited in the same county where his crime was committed, the ward of a recently transplanted parole officer, Emily Smith (Brenda Blethyn). But the odds are against Garnett, who still has something of a temper. Sheriff Bill Agati (Harvey Keitel) has a deep seated grudge against Garnett all these years later, since the murdered deputy was one of his men. Doing his best to undermine Garnett’s newfound stability, Smith picks up on the Sheriff’s intentions and does her best to circumvent. But Garnett also must contend with criminal friends from his past life (Luis Guzman), intent on drawing him back into the fold.

Two Men in Town is actually a remake of the 1973 film of the same name starring Alain Delon and Jean Gabin, directed by Jose Giovani (better known as the author of the source material that would result in Jacques Becker’s Le Trou, 1961, and Claude Sautet’s Classe Tous Risques, 1960). Transported to modern day New Mexico, illegal immigration provides the framework for Bouchareb’s update and, as is his general fashion, he clangs a host of cultural and religious ideals altogether in one big blender. As the Muslim converted ex-con, Whitaker exudes a hangdog weariness befitting of this scenario, but the screenplay undermines him at every clunky, grinding turn. Rather than focus on a series of characterizations that could have been smartly realized, Bouchareb favors the overarching message of a flawed justice system. For instance, trapping Garnett in the same county where he committed his crime, or the hothouse of barely dealt with immigration issues. But that doesn’t mean the remainder of the film has to adopt a corresponding lack of logic, such as the ridiculous romance established with Dolores Heredia, or a pair of stock villains, like the hurriedly drawn Luis Guzman or the vengeful Sheriff played by Keitel.

Bouchareb’s script takes pains to paint Keitel as a complicated, conflicted individual, which sometimes feels too obvious, like when he sobs over the bodies of dead immigrants in the desert, with signs of an infant being stolen tipping him over the emotional edge.

While the film does a disservice to Whitaker, the force that takes all of her scenes by rapturous storm is Brenda Blethyn as a no-nonsense yet kind hearted parole officer who goes head to head with the gruff Sheriff. But her energy is like a raging fire burning through tinder, a mere puff of smoke that does little to stave off the film’s predictability. A late ‘surprise’ comes in the form of Ellen Burstyn’s reveal, who gives an otherwise standard scene a bit of emotional heft—if only we weren’t a bit distracted by how exactly she fits into the Garnett’s narrative.

Bouchareb replaces DoP Christophe Beaucarne from Woman with another leading French cinematographer, Yves Cape (responsible for several Dumont title as well as Leos Carax’s Holy Motors), who turns New Mexico into a beautiful yet hopelessly arid and unwelcoming landscape. The opening and closing shots of the film, which create a sort of inverted finale to the standard Western tropes Bouchareb is evoking by featuring a character striding off into the sunrise. While that may be a genre predicated on notions of fate, there isn’t any real challenge to this irrevocability, making the film’s more obvious talking points absolutely moot.

★★½/☆☆☆☆☆