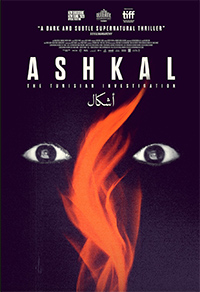

Death in the Garden: Chebbi Debuts Eerie, Nuanced Murder Mystery

In a supremely frightening sense, the events transpiring in Ashkal (which means ‘shapes’ in Arabic) recalls both the ideas outlined in James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time and the opening line of Fahrenheit 451; “It was a pleasure to burn.” Only, where Ray Bradbury was referring to books, Youssef Chebbi’s film concerns the burning of humans via self-immolation. Tying his narrative to the overthrow of Tunisia’s dictator Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali in 2010, instigated by the self-immolation of street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi (which catalyzed the larger scale events termed the Arab Spring), Chebbi paints a picture of a new but troubled democracy overshadowed by the recent past, as evidenced by the ongoing political crises involving President Kais Said’s various actions some have regarded as a self coup. Although the subtexts are culturally specific, it’s an effective use of genre as a medium to explore contemporary despair to which there is no clear cut resolution.

In a supremely frightening sense, the events transpiring in Ashkal (which means ‘shapes’ in Arabic) recalls both the ideas outlined in James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time and the opening line of Fahrenheit 451; “It was a pleasure to burn.” Only, where Ray Bradbury was referring to books, Youssef Chebbi’s film concerns the burning of humans via self-immolation. Tying his narrative to the overthrow of Tunisia’s dictator Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali in 2010, instigated by the self-immolation of street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi (which catalyzed the larger scale events termed the Arab Spring), Chebbi paints a picture of a new but troubled democracy overshadowed by the recent past, as evidenced by the ongoing political crises involving President Kais Said’s various actions some have regarded as a self coup. Although the subtexts are culturally specific, it’s an effective use of genre as a medium to explore contemporary despair to which there is no clear cut resolution.

At the beginning of the Revolution, construction was halted on a newly initiated Tunisian district intended for dignitaries of the old regime, a stillborn city named the Gardens of Carthage. In the decade since, construction has slowly resumed. However, when the burnt body of an elderly gentleman is found in one of the lots, cops Fatma (Fat Oussaifi) and Batal (Mohamed Grayaa) are assigned to investigate. It appears to be suicide by self-immolation, though this recalls the act which kicked off the Revolution in 2010, making everyone immediately wary. Worse, signs indicate there was no gasoline and the man appeared not to have struggled. Scouring through internet footage, it appears the victim may not have been alone, and Fatma is convinced there is foul play. Then, a young woman’s body is also found, killed the same way, shortly after followed by a fellow police officer. The more Fatma digs, the more resistance she is met with, until the continually puzzling clues lead her to a point of no return.

Chebbi steps out on his own with Ashkal after having co-directed last year’s Black Medusa with Ismael, also a narrative which centers on the realities and struggles faced by Tunisian women (albeit in a narrative reminiscent of Belle de Jour or Crimes of Passion, where women are forced to seek pleasure in the form of a separate alter ego). His latest, co-written by Francois-Michel Allegrini, builds their intensity around the resilience and tenacity of newcomer Fatma Oussaifi, who must combat blatant misogyny as well as mistrust of the police as a whole within the community.

More than deciphering the mystery of the film, Ashkal is also a procedural on women occupying positions of power as merely a facade in what’s considered the only democratic Arab nation. Where the film is most unsettling are in the smaller details, often the hints and suggestions of clues just out of frame. A composite of the suspect who is ‘giving’ these people fire recalls the mask in Hiroshi Teshigahara’s identity thriller The Face of Another (1964), while Chebbi effectively wields social media as a tool for discomfort. Eventually, it appears this is an allegory for mass hysteria, like the Pied Piper of Hamlin or the urban legend about lemmings committing mass suicide (where the Biblical allusions of the flood and later the prophesied fire also checks).

Going back to the specific neighborhood and incomplete infrastructure of the Gardens of Carthage, where abandoned vestiges of a corrupt regime are still resolutely and visibly unavailable to the people, Chebbi’s motif recalls Shelley’s Ozymandias—“…Round the decay/Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare/The lone and level sands stretch far away.” These monuments intended for the elite are all that remain of their empty glory. Lensed by Hazem Berrabah, the final shot of Ashkal may not provide the concrete answers some may demand, but it’s a chilling, arresting glance into the abyss.

Reviewed on May 25th at the 2022 Cannes Film Festival – Directors’ Fortnight. 92 Mins

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆