Particle Decay: Satrapi Explores Curie in Elliptical, Stunted Biopic

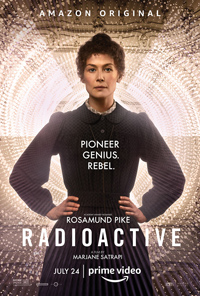

The persona of Marie Curie is a no-brainer as far as cinematic importance and appeal goes, so her resurrection courtesy of Marjane Satrapi in Radioactive, the filmmaker’s fifth narrative feature, promised to be a good fit considering the Polish born scientist conducted her research in France. However, something feels consistently off and underwhelming in the alchemy of this latest endeavor, which finds Rosamund Pike playing a prickly composite of the brilliant woman in the English language.

The persona of Marie Curie is a no-brainer as far as cinematic importance and appeal goes, so her resurrection courtesy of Marjane Satrapi in Radioactive, the filmmaker’s fifth narrative feature, promised to be a good fit considering the Polish born scientist conducted her research in France. However, something feels consistently off and underwhelming in the alchemy of this latest endeavor, which finds Rosamund Pike playing a prickly composite of the brilliant woman in the English language.

In its attempt take futuristic departures to convey the ripple effects, both negative and positive, of Curie’s discoveries, Satrapi and scribe Jack Thorne split the process of the biopic in ways which seem interesting but tend to negate the human essence of their subject.

Based on the graphic novel by Lauren Redniss and adapted by Jack Thorne (The Aeronauts, 2019), Polish émigré Maria Sklodowska (Pike) experiences trouble finding a proper lab while studying at the Sorbonne, partially due to being a woman in 1891 Paris. Changing her name to Marie, a chance flirtation with Pierre Curie (Sam Riley) leads to a professional and romantic relationship. Together they discover radium and polonium, which sees them awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics.

After her husband’s untimely death, she would go on to win the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1911 for isolating pure radium. She would also embark on an affair with the younger, married Paul Langevin (Aneurin Barnard), furthering the ill-will bestowed upon her in France. She is the first woman to have received the Nobel Prize and the only person to have received the prize in two different fields.

Marie Curie feels like one of the figures who would have made a novel subject in 1980s cinema, where leading ladies like Spacek, Fonda, Weaver, Streep and Lange spearheaded biopics of notable women in significant performances. Since her breakthrough in Fincher’s Gone Girl (2014), Pike has navigated towards these comparable kinds of vehicles, such as an underrated performance as Marie Colvin in A Private War (2018).

As Curie, Pike is limited to the parameters Thorne’s chalky script provides, and when she isn’t anguishing at the social constrictions which limited her, we’re treated to a host of repetitive and eventually grating scenarios which reduce her to a self-obsessed social disease who tends to aggravate all those who come in contact with her. Introduced on her death bed in 1934, Pike’s papery make-up is reminiscent of old 1950/60s B-movies, like Coleen Gray’s aged alcoholic in The Leech Woman (1960).

Most of the film’s developments on her personal relationships are a chore to sit through, marinated in clichés and highlighting moments of banality. A courtship with Riley’s Pierre Curie (recalling John Hurt) could have been excised altogether to better focus on an intensely interesting period of her life, between Nobel prizes, embarking on an affair with her dead husband’s younger married colleague Paul Langevin (an equally underwhelming role for Aneurin Barnard) and at the point where she’s the subject of considerable ire by the French who tried repeatedly to diminish Curie and her research.

The anti-Semitism of the period is glossed over, and to equal the rosy, superficial hue is some surprisingly chintzy cinematography from Anthony Dod Mantle (Slumdog Millionaire, 2008; Antichrist, 2009) in a production which looks like a glossy history channel reenactment. However, Radioactive isn’t without some choice flourishes, and Satrapi’s attempts to convey the legacy of Curie through tangents like the atomic bomb testing in the desert, the tragedy of Chernobyl, and chemotherapy suggest a more interesting mixture of Curie and her work than what is presented here. It’s as if Satrapi and Thorne were nervous about presenting their subject on terms Curie would preferred, boiling her down to digestible pulp.

Pike is obviously not the first person to portray Curie on screen, but her approximation is about as glossy as the Greer Garson version from 1943. The inimitable Isabelle Huppert played Curie in 1997, an inspired casting choice, while Polish actress Karolina Gruszka most recently in 2016. But this version, not unlike the recent Harriet Tubman biopic, reduces Curies to an idea, a Ryan Murphy-esque fantasy of superficial revisionism.

In the film’s third act, where her adult daughter Irene, played by Anya Taylor-Joy (who shares some painfully written dialogue—“it’s time to make this war your war!”), Curie’s work in establishing the need for x-rays on injured soldiers becomes reminiscent of G.W. Pabst’s Paracelsus (1943). A moody, ambient score from Evgueni and Sacha Galperin works well in some of the tonal shifts, but Satrapi’s inclusion of two highly recognizable pieces of Philip Glass only assists in further distracting from the film.

★½/☆☆☆☆☆