Reviews

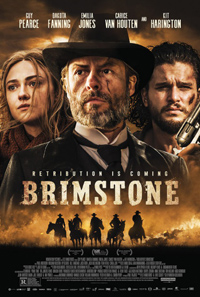

Brimstone | Review

The Love of a Preacher Man: Koolhoven’s Pseudo-Feminist Western an Ambitiously Grotesque Affront

Unveiling the most expensive Dutch film production since Paul Verhoeven’s Black Book (2006), Martin Koolhoven’s epically structured Brimstone is a dizzying revision of the spaghetti Western, prizing the perspective of a female protagonist (although no less rape filled than the frames of Sergio Leone) and featuring a concoction of varied international flavors in this cruel portrait of the American frontier. Koolhoven recreates unrelenting misogyny to batter his audience into submission with this grotesque female bildungsroman of a mute prostitute’s valiant struggles to exert willful agency despite considerable domestic violence, the director divorcing himself from any semblance of the kind of restraint seen in his lauded 2011 box office darling Winter in Wartime.

Unveiling the most expensive Dutch film production since Paul Verhoeven’s Black Book (2006), Martin Koolhoven’s epically structured Brimstone is a dizzying revision of the spaghetti Western, prizing the perspective of a female protagonist (although no less rape filled than the frames of Sergio Leone) and featuring a concoction of varied international flavors in this cruel portrait of the American frontier. Koolhoven recreates unrelenting misogyny to batter his audience into submission with this grotesque female bildungsroman of a mute prostitute’s valiant struggles to exert willful agency despite considerable domestic violence, the director divorcing himself from any semblance of the kind of restraint seen in his lauded 2011 box office darling Winter in Wartime.

A more fitting title for this gruesome indictment on the hypocrisy and inevitable perversion of unchecked religious zealotry would have been something like the 1629 play by John Ford, ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore (which was made into a film version in 1971 starring the handsome likes of Fabio Testi and Charlotte Rampling in the throes of incestuous desire) but masquerading as the nastier, sacrilegious sister of Campion’s The Piano (1993) with all the subtlety of Refn. Divided into four distinct segments, Koolhoven’s narrative gets a little hoary (no pun intended) by the third chapter (each named for Biblical insinuations), which is unfortunate considering the intensely administered, incredibly disturbing build-up and an ultimately transfixing turn from Dakota Fanning.

A mute midwife in her isolated rural farming community, Liz (Fanning), seems to enjoy a peaceable existence with her husband (William Houston), doting on her young daughter (Ivy George), while her adolescent step-son (Jack Hollington) keeps a notable distance. When a new Reverend (Guy Pearce) appears at the pulpit one Sunday, Liz is immediately alarmed, and it seems she has been marked to be the scapegoat for some of that old time religion. Right after the new shepherd delivers a sermon on hellfire and damnation, Liz is backed into a corner when forced to assist a woman in labor on the church floor. But because the baby’s head is too big, she must choose to save the mother or the child. Unfortunately, the townsfolk aren’t too keen about her decision, the Reverend using the opportunity to turn it into a suffocating tide of resentment driving the family out of town. And then, the narrative goes further back in time, to reveal Liz as a young girl named Joanna fleeing something dangerous, swept into the sex trade as a young prostitute, until her past catches up with her.

The malevolence exuding from the early frames of Brimstone is palpable, and it’s where Koolhoven’s slighter brushes with the grotesque are most effectively chilling, such as Fanning’s fateful decision to save a mother or her baby (it turns out she was cursed long before this moment) during an unfortunate birthing reality, later bookended by disemboweled pregnant sheep. The juxtaposition of religion and pagan, as Guy Pearce’s formidable Reverend finds himself immediately at odds with Fanning’s morose and muted mid-wife, suggests a plentitude of anxious tension in the build-up. Whether or not we’re meant to believe she’s a witch, this leads us to the brutal side of the menacing horrors women have endured through eons of masculine based, religious doctrines.

But tragic bloodshed is a segue into a second chapter, where Emilia Jones appears as the younger version of Fanning’s Liz, now known as Joanna, a waifish vagabond immediately trundled off by some Chinese immigrants and sold into sex slavery run by Paul Anderson’s hard-hearted Frank. Here, the film takes a hard left into exploitation territory, beginning immediately with some salty dialogue courtesy of some sinister prostitutes. These sequences are often redeemed thanks to some impressive acting from a set of international actresses, including Sweden’s Vera Vitali (who recalls Anna Levine’s tortured prostitute from Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven, 1992), and Germany’s Carla Juri (of the outré Wetlands and recently, Chad Hartigan’s Morris From America). And if more despairing violence ends up being more-or-less defensible in the narrative’s mounting ludicrousness, we suddenly revert even farther back into Joanna/Liz’s child-development in a reverse linear switcheroo. And it’s here where all of Brimstone’s viciousness gets long in the tooth, and becomes victim of its own desensitization.

In case Pearce wasn’t abusive enough for you in the earlier sequences, he’s back to terrorize Carice Van Houten as Joanna’s mother. The role isn’t much for Houten to play with, and perhaps, more notably it reunites her with her Game of Thrones co-star in a brief and underwhelming role for Kit Harington as a swarthy but laudable outlaw who hides out in the Reverend’s barn for a few days while Joanna cares for him in secret, developing her first sexual feelings for a man.

Koolhoven’s frequent morbidity isn’t the problem with Brimstone, which has a lot more in common with exploitation classics of the 1970s (a Western tinged I Spit on Your Grave) than it does the Western feminist prototypes of Nicholas Ray, John Ford, Samuel Fuller, or Anthony Mann, who gave actresses like Joan Crawford (Johnny Guitar), Anne Bancroft (7 Women) and Barbara Stanwyck (The Furies and Forty Guns) the keys to the kingdom.

Koolhoven does seem inspired by plenty of his more offbeat predecessors, such as the watchful, resilient Fanning keeping guard in a rocking chair against the boogeyman in the woods, which feels very Lillian Gish in The Night of the Hunter (1955). And there’s a certain inconsistency between some of its shifts, although giving an ambitious character palette for Fanning, it doesn’t explain some elements, like how she came to be such a skilled and token mid-wife. Perhaps more evident of these slights in detail is the characterization of Pearce’s Reverend, initially the personification of a demon, and eventually more the perverted, incestuous version of Arthur Dimmesdale (which ends in a fiery rage trumped by a silly line uttered during an illogical moment).

Still, this is an impressive bit of spectacle, lensed by Neil Labute’s regular DP Roger Stoffiers, and appropriately period detailed thanks to returning production designer Floris Vos (who was on hand for Winter in Wartime). As degrading as it is empowering, both the sheer ambitiousness of Koolhoven’s narrative arc and the impressive performance from Dakota Fanning are reason enough to seek out this jarring blend of elements which hearkens back to a more daring period in cinema.

Reviewed on January 7 at the 2017 Palm Springs International Film Festival – 148 Mins.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Los Angeles based Nicholas Bell is IONCINEMA.com's Chief Film Critic and covers film festivals such as Sundance, Berlin, Cannes and TIFF. He is part of the critic groups on Rotten Tomatoes, The Los Angeles Film Critics Association (LAFCA), the Online Film Critics Society (OFCS) and GALECA. His top 3 for 2021: France (Bruno Dumont), Passing (Rebecca Hall) and Nightmare Alley (Guillermo Del Toro). He was a jury member at the 2019 Cleveland International Film Festival.