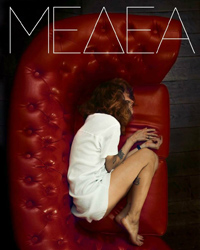

Who Could Kill a Child?: Zeldovich Explores a Fearful Symmetry in Modernized Tragedy

Russian director Alexander Zeldovich’s filmography is something of a curiosity unto itself, which feels more apparent than ever in his fourth feature, Medea. As its title suggests, this is a take on the classic Greek tragedy, originally penned by Euripdes in 431 BC, birthing one of the most notorious and everlasting female archetypes of a woman scorned (hell, it seems, still has no fury like her).

Russian director Alexander Zeldovich’s filmography is something of a curiosity unto itself, which feels more apparent than ever in his fourth feature, Medea. As its title suggests, this is a take on the classic Greek tragedy, originally penned by Euripdes in 431 BC, birthing one of the most notorious and everlasting female archetypes of a woman scorned (hell, it seems, still has no fury like her).

Usually taking about a decade between features, Zeldovich has previously been enamored with Vladimir Sokorin, last on hand in 2011 with Target, an adaptation which has sci-fi tinged Anna Karenina vibes. In this iteration of the famed tale, the eponymous infanticide-prone tragedienne is transplanted to Israel, a Holy Land which bears interesting thematic fruit in the region’s monotheistic tendencies juxtaposed with the polytheistic, mythological origins of the narrative. Skittering across cultural corruptions, religious fantasies and compulsive sexual tendencies, this odd melange of subtexts is a transfixing portrait of madness and desperation, and surprisingly unpredictable given the inevitability demanded by the infamous murderess’ fate.

We’ve seen Medea through many cinematic iterations, from Pier Paolo Pasolini to Lars Von Trier, embodied by the likes of Maria Callas and Isabelle Huppert. She’s an eternal literary and cinematic fixture, and one whose horrifying actions tend to strip away the empathy afforded a woman wronged. In the original myth, Medea was a sorceress, daughter of King Aeëtes, who screwed her family over to assist Jason obtain his Golden Fleece, only to find herself abandoned after her usefulness passed. A stranger in a strange land, she murders her children in retaliation for her lover’s actions.

There are contemporaneous similarities here, with Medea (Tinatin Dalakishvili) narrating her own story as a sort of expiation to an absent confessor (suggesting there’s no god, or at least not one interested in bearing witness to her perspective). She has a degree in Chemical Technologies, but has allowed herself to become the concubine of the powerful Alexey (Evgeniy Tsyganov). After finally deciding to leave his wife, the puritanical Nadya, Alexey decides to embrace his Jewish heritage and relocate with Medea to Israel, the promised land (the greener pasture which will allow them to escape the corrupting forces of Mother Russia, ‘the last winter’ of their lives). But certain underhanded dealings with Medea’s brother, FSB Officer Valery, threaten their promising future. When Valery threatens to extort Alexey, his sister murders him, thinking nothing of her actions until his corpse is later discovered, necessitating she confide in her husband. Unfortunately, Alexey is dismayed, and their increasing emotional estrangement causes him to leave her.

Zeldovich leans into the mythological roots of the narrative with a pronounced zeal for Medea’s undefined mysticism, perhaps enhanced by the striking presence and performance of Georgian actress Tinatin Dalakishvili (a favorite of Anna Melikyan, having appeared in 2014’s Star and last year’s Fairy). With blonde brow and brunette locks, her arresting visage is the gateway to a plunge into the abyss, experimenting with the strange bedfellows of sexuality and religion, both escapist crutches she’s unable to wholly commit to. Curiously, she falls into hypnotic trances during orgasm, a signal which defines her increasingly aggressive trysts, and is eventually absent in her final moment of lovemaking with Alexey, their emotional reality obfuscating her ability to experience physical pleasure.

Early on, discussions of happiness are referenced from a previous Soviet film (potentially Aleksandr Medvedkin’s 1935 silent film Happiness), but eventually, it’s revealed neither of them really understands the other. Their folly is further symbolized via a gifted wristwatch to Medea, which encapsulates trinkets shaped as the sun, moon and stars. Eventually, the clock stops working, signaling the end of Alexey’s love, leading her to have it programmed to turn counter clockwise in a defiant reversal to a better time (unfortunately they’ve gone beyond the pale of the sentiments in something like Cher’s “If I Could Turn Back Time”).

Medea’s descent eventually becomes more visually lavish, with some magical realism indicating she’s indeed lost her head, and cryptic references to Judaism tenets regarding women’s hair. “Do you know what will be next?” someone asks her, a nod to her ability to predict certain moments before they happen. Of course she does, and we’re also a part of her preternatural realm regarding the denouement, set drastically amongst a tourist spectacle overlooking ruins (like the arid version of a famous sequence in the vibrant Marilyn Monroe noir Niagara, 1953), where her shrieking remonstrance manages to haunt even though we’re fully aware from the first frame where this tale will lead.

Shot by Zeldovich’s favored DP Aleksandr Ilkhovksy (who also lensed Ilya Khrzhanovsky’s masterful 2004 film 4), Medea is a visual odyssey of continually diminished landscapes, leading to a fiery zenith on a rooftop representing the final straw between estranged husband and wife. Her crumbling romance is matched by the disintegrating facades and infrastructures, to a fitting temple whereby a modernized tale retreats to its age-old, universal fount of fury.

Reviewed virtually on August 9th at the 2021 Locarno Film Festival – Concorso Internazionale. 139 Mins

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆