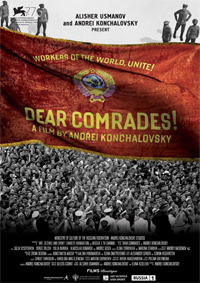

24-Hour Party People: Konchalovsky Examines Propaganda and Protests in Reenactment of Infamous Massacre

Sporting one of the most fascinating filmographies of any Russian (or any other) auteur, Andrey Konchalovsky returns with Dear Comrades!, his third period piece in row following Paradise (2016) and Sin (2019), which was filmed in Italian. Resurrecting another dark chapter of Soviet history with this reenactment of the 1962 massacre of protestors in Novocherkassk, Konchalovsky utilizes his late period muse Julia Vysotskaya once again to frame a narrative about shifting allegiances when the violence lurking beneath the façade of bureaucracy is utilized to keep the status quo despite considerable human collateral damage.

Sporting one of the most fascinating filmographies of any Russian (or any other) auteur, Andrey Konchalovsky returns with Dear Comrades!, his third period piece in row following Paradise (2016) and Sin (2019), which was filmed in Italian. Resurrecting another dark chapter of Soviet history with this reenactment of the 1962 massacre of protestors in Novocherkassk, Konchalovsky utilizes his late period muse Julia Vysotskaya once again to frame a narrative about shifting allegiances when the violence lurking beneath the façade of bureaucracy is utilized to keep the status quo despite considerable human collateral damage.

A narrative contained within the confines of several days in early June of 1962, it’s another lusciously realized exercise from Konchalovsky in film beautifully photographed and formidably choreographed resulting in another masterwork of the historical grotesque.

On June 1, 1962, a strike takes place amongst the workers at an electromotive factory in the provincial town of Novocherkassk in the South of the USSR. Lyudmila (Vysotskaya), a Communist party official and WWII veteran devoutly follows the wishes and ways of the Party, and along with her colleagues, including Loginov (Vladislav Komarov), a man with whom she is intimate, is mollified by what the strike means for them from higher ups in the party, all the way to Khrushchev. At home, Lyudmila supports her vodka-swilling father (Sergei Erlish) and rebellious daughter Svetka (Yulia Burova), who is one of the protestors. When gunfire erupts and the protest turns into a massacre, Lyudmila barely survives and is unable to locate the whereabouts of her daughter. With the unlikely assistance of a sympathetic KGB member (Andrei Gusev), Lyudmila finds her allegiance to the Party waning as the search for her daughter is stymied by the immediate cover-up of both the protest and the killings while unidentified corpses are carted secretly out of the area while the town is locked down.

Not surprisingly, the marketing of Konchalovsky often clings to his early associations with Tarkovsky, having written the iconoclast’s first two features (uncredited on Ivan’s Childhood but responsible for the framework of Andre Rublev) before he branched off on his own. Tackling Chekov’s Uncle Vanya (1970) and then mounting his historical masterpiece Siberiade (1979) before a stellar track record of English language features, both mainstream (Runaway Train, 1985) and strange (Shy People, 1987; Homer & Eddie, 1989) before the troubled production of 1991’s Tango & Cash forced him out of Hollywood and back to the Motherland, where his career experienced another renaissance over the past decade thanks to several lauded titles, including The Postman’s White Nights (2014) and the grueling but underrated Holocaust drama Paradise (2016). This latest, if it warrants any comparison, feels akin to that latter title, as it once again weights the narrative on the performance of Vysotskaya and is once more penned by Elena Kiseleva (who has penned his last four scripts). Much like she was in Paradise, Vysotskaya is the anchor, fashioning a character arc not unlike the slyly subversive Stalinist pilot-turned-teacher Mayya Bulgakova in Larisa Shepitko’s classic Wings (1966)

Initially, Dear Comrades! begins like the pages of a propaganda pamphlet, with staunch communist Lyudmila decrying anything remotely anti-Soviet (“the party’s words are law”) and going so far as to call for the execution of those pesky protestors (she, of course, isn’t exactly following all the rules of a good Communist by having an affair with her married superior).

Whispers of Khrushchev’s inability to quell the unrest of the people, whose rations are dwindling and are more expensive than ever (at odds with the low costs of goods under Stalin, even during wartime) strike fear in the hearts of the local party members, who know they will be blamed for being unable to contain the protestors. Our eyes and ears in this are Lyudmila, and when all hell breaks loose on the peaceful protestors (which feels eerily similar to what’s happening in the U.S. right now, of course), she stumbles upon KGB official Viktor opening fire on the protesting citizens.

The resulting sequence in the town square is Konchalovsky’s piece de resistance in Dear Comrades!, and it’s where Andrei Naidenov’s (Euphoria, 2006) crisp black and white photography conveys the greatest bite of Soviet coldness, the pandemonium in the slaughter juxtaposed by Lyudmila’s escape into a nearby building while those alongside her are decimated.

The re-creation of the early 1960’s on film is well-attenuated, but more so the stylistic cinematic choices Konchalovsky makes. There are several striking shots of Vysotskaya, who appears ageless, reduced to a terror which recalls visually and performatively the memory of Tatyana Samoylova in The Cranes Are Flying (1957). As we see both the rebellion of Lyudmila’s daughter and father (in one droll sequence, Gusev’s KGB agent visits her apartment to find the old man getting drunk and wearing his old army uniform, a punishable offense—she explains ‘grandpa is being funny’), Dear Comrades!, and its cheery exclamatory is more a subversive exercise on when and how we learn to tell the truth and when to lie in the service of self-preservation.

Lyudmila’s teary epiphany of “What am I supposed to believe in if not Communism?” when she learns her own party most likely threw her daughter’s corpse into a grave marked with someone else’s name, leads the narrative to a queasy precipice as concerns her future. Arguing with her father, she remarks there’s nothing the state can do which will scare her—after all, she’s read Sholokhov. But as her father remarks, had Sholokhov published certain truths, he would have been executed. In one of Konchalovsky’s cruelest juxtapositions, an overwhelmed Lyudmila glances upon a dog nursing a litter of puppies amidst the chaos of human strife, suggesting connection and survival are the natural course of every animal besides and despite mankind, constantly imperiled by the violence wrought through persistent ideologies and political agendas.

Reviewed virtually on September 7th at the 2020 Venice Film Festival. Main Competition – 120 Mins

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆