Female Misbehavior: Erlingsson Explores Ecofeminism in Entertaining Character Portrait

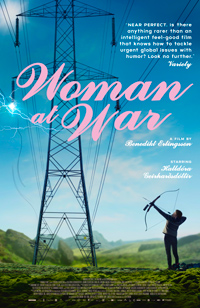

After exploring the defining social elements between humans and their horses in his homegrown debut Of Horses and Men (2013), Iceland’s Benedikt Erlingsson scores an equally droll success in a sophomore film about communal resistance to corporate intrusion with Woman at War. Reuniting with actress Halldóra Geirharðsdóttir, here on double duty as a set of twins, Erlingsson concocts a generous mix of social commentary, character development, and emotional pathos laced with a series of slapstick comedic turns. It’s a rare successful mixture of topical grandstanding and playful tonality headed by a winning lead performance by the flinty Geirharðsdóttir, which has already generated plans for a Jodie Foster led English language remake well before its US theatrical premiere. Instilled with a defining streak of dry, Icelandic humor, Erlingsson’s universality with his narrative scope ensures broad likeability for a sophomore effort as meaningful as it is pleasurable.

After exploring the defining social elements between humans and their horses in his homegrown debut Of Horses and Men (2013), Iceland’s Benedikt Erlingsson scores an equally droll success in a sophomore film about communal resistance to corporate intrusion with Woman at War. Reuniting with actress Halldóra Geirharðsdóttir, here on double duty as a set of twins, Erlingsson concocts a generous mix of social commentary, character development, and emotional pathos laced with a series of slapstick comedic turns. It’s a rare successful mixture of topical grandstanding and playful tonality headed by a winning lead performance by the flinty Geirharðsdóttir, which has already generated plans for a Jodie Foster led English language remake well before its US theatrical premiere. Instilled with a defining streak of dry, Icelandic humor, Erlingsson’s universality with his narrative scope ensures broad likeability for a sophomore effort as meaningful as it is pleasurable.

Halla (Geirharðsdóttir) is a beloved member of her quaint rural Icelandic community as the local choir director. Little do they suspect she is what the press have termed the “Mountain Woman,” the environmental activist who has been waging war on the newly developed aluminum factory which has sprouted up nearby, threatening to continue a troubling trend and encroach on their way of life. But the greater damage Halla inflicts on the company, the more the government responds in kind, bringing in satellite cameras and heat-sensing helicopters to capture her, since her actions have caused Chinese investors to potentially pull out of the investment. But just as her activism reaches a tipping point, where her involvement will inevitably lead to her capture, Halla receives word her application for adopting a child from the Ukraine has finally been accepted, which also involves her twin sister Asa (also Geirharðsdóttir). Desperate to fulfill both personal obligations, Halla reaches the point of no return.

Erlingsson joins a growing myriad of surging Icelandic directors whose works have been benefitting from ecstatic word of mouth across the festival circuit, including Hafsteinn Gunnar Sigurðsson’s Under the Tree (2017), Rúnar Rúnarsson’s Sparrows (2015) and Grimur Hakonarson’s Rams (2015).

Notably, Erlingsson concocts a surprisingly intact portrait of ecofeminism, the duality of Halla and Asa combining ecological concerns with feminist ones. Halla’s rebuke of male domination concerns not only the environmental decimation anticipated by corporate takeover she so desperately wishes to avoid, but also her own body and domestic sphere, which she has defined in the absence of masculinity evidenced by the film’s dramatic crux of her struggles to adopt an orphaned Ukrainian girl. Sacrifice is also at the heart of Woman at War, in both the realm of comfortability vs. ideals and the compassionate and unconditional support of female fraternity (which is to say, the less one knows about the character dynamics and interactions of the film, the sweeter its pulpy twists).

Stylistically, Woman at War’s straightforward approach is benefitted by Erlingsson’s choices to have the score portrayed visibly on screen from three musicians playing various instruments meant to heighten and estrange us from the danger of Halla’s actions. They’re later joined by a Ukrainian singing trio in this diegetic mise en scène, which adds to the sense of globalization as an undercurrent (Erlingsson also pokes at Iceland’s own parochial outlooks in the figure of Juan Camillo Roman Estrada, the lone foreigner authorities are automatically suspicious of, who was part of the director’s Of Horses and Men).

Broaching serious subjects without taking itself too seriously (one needs look no further than Halla’s Nelson Mandela mask, one of her beloved icons), Woman at War presents a fascinating and fierce characterization whose contradictions and complexities allow for a compelling enterprise.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆