In Search of Lost Time Regained: Kaufman Mutates Memory and Meaning

“The real voyage of discovery consists of not in seeking new lands but seeing with new eyes,” advised Marcel Proust, one of many countless bits of quotable wisdom from the prolific French novelist, one of the major literary influences of the twentieth century. Proust, like James Joyce, doesn’t happen to be one of the many diegetic references in the hyper-literate I’m Thinking of Ending Things, the latest exercise in narrative collapse and disorienting fugue states from Charlie Kaufman.

“The real voyage of discovery consists of not in seeking new lands but seeing with new eyes,” advised Marcel Proust, one of many countless bits of quotable wisdom from the prolific French novelist, one of the major literary influences of the twentieth century. Proust, like James Joyce, doesn’t happen to be one of the many diegetic references in the hyper-literate I’m Thinking of Ending Things, the latest exercise in narrative collapse and disorienting fugue states from Charlie Kaufman.

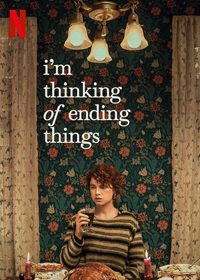

The third directorial effort from Kaufman, following Synecdoche, New York (2008) and Anomalisa (2015) is based on the lauded 2016 novel by Canadian writer Iain Reid, but slides like hand in glove to the oeuvre of the writer responsible for Spike Jonze’s Being John Malkovich (1999), Adaptation. (2002) and the beloved Michel Gondry pic Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004).

Even more desperate and less poignant than the melancholic intersections of art and humanity than his previous efforts, this is a study in the faultiness of memory, fantasy, projection and the mutable designs of what we like to call truth. It would behoove one to pay close attention to the contradictions and constant fluctuations which overwhelm, subdue and even suffocate in a film which seems to start off in familiar, logical territory before we’re caught in an endless eddy of collapsing perceptions. But like all of Kaufman’s offerings, it’s an exercise worth revisiting, although not so much for enjoyment rather than a means to quell the discomfiting precipice of dread it leaves us stranded upon.

A young woman (Jessie Buckley), whose name may or may not be Lucy (as we glean from a reference to a Wordsworth poem) is having second thoughts about her relationship with Jake (Jessie Plemons), a young man she’s been dating for an inordinate amount of time (we’re given a few different answers). But she’s agreed to visit his parents in Oklahoma, and so they set off on their first long road trip together on a wintry day as a blizzard looms.

The closer they get to his parents, the more she’s convinced herself she’s thinking about ending things with Jake. Upon arrival, it seems his parents (Toni Collette, David Thewlis) never really extended an invite, and upon meeting their son’s girlfriend, it appears something is off. From moment to moment, Mother and Father appear to be either rapidly aging or regressing to more youthful times, and Lucy, who maybe is actually Amy, is having a hard time convincing Jake to leave. When they finally do, some kind of transformation has taken hold of the young woman—she no longer seems to be herself. As they return to the quietness of the dark, snowy roads, they stop for a blizzard, wherein another uncomfortable interaction transpires. At a loss for where to throw away their sticky cups of melting liquid, Jake takes the young woman to his old high school, where we reunite with a lonely janitor (Guy Boyd), who may or may not actually be Jake, and whose own invisible trajectory has been transposed (or paralleled) with the dinner visit.

“Time passes through us,” is one angle of a fluctuating idea about what we define as time, as uttered by Jessie Buckley when both she and the audience believe her name to be Lucy. But then time is all about the perspective being utilized, something we’re also not quite sure of in this elaborately unspooling ballet of memory, more or less presented in four lengthy swaths, two of which transpire in a cramped jalopy on a miserly plateau of snowy country roads.

As is often the case with Kaufman’s scripts, the film is littered with striking trinkets which lodge in the memory. Initially, this is a familiar story for anyone who’s deigned to end a relationship going nowhere, and we’re lulled into the paradigm of Lucy’s dark poetry (“the sun goes up and down like a tired whore,” is one of many bon mots from her recitation of “Bonedog,” an actual poem by Eva H.D.). Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, David Foster Wallace’s essay on television, Oscar Wilde, and Guy de Borde are all explicated in conversation, as is the difficulty in perceiving the mood or tone from abstract art—we are constantly turned back to the participating party, i.e., the audience member, the critic, the observer and the implications of their own interpretations.

When next in the car, the poet Lucy (now maybe desperate to return home to either be on time for her shift as a waitress or work on her dissertation) gives a striking monologue which happens to be Pauline Kael’s infamous pan of Cassavetes’ A Woman Under the Influence (1974). A surprise stop at a late night stand for blizzards while they’re in blizzard yields another Kaufman key – Anna Kavan’s famed novel Ice, a prototype of eco-feminist horror about the world as an apocalyptic wasteland in which a man pursues a waif no longer interested in his advances. Kavan, often credited as a sister to Kafka, has her own interesting history of drastic reinvention, but Kaufman’s formulations are closer to her fluctuating portrait of a world on a wire rather than Kafka, more often interested in examining the overwhelming relationship of a character to a vaguely established, menacing institution. In Kavan, the whole world and those who move around in it are suspect.

It’s unnecessary to divulge every bit of meaning from every formidable and thought provoking reference in I’m Thinking of Ending Things, but needless to say, perhaps “sometimes a thought is closer to the truth,” if at the very least, because it is “thought,” and in the collapsing realities of the film, a “thought,” like a virus, is something which desires to “live.”

Buckley, who was excellent in recent items such as Beast (2017) and Wild Rose (2018) is initially our supposed focal point—she succeeds in channeling the right balance of disconnectedness and empathy which makes everything seem disconcerting. Plemons eventually takes over, as we’re left wondering if the school janitor who keeps breaking into the narrative is actually him. Is the voice of Oliver Platt, both calling Lucy/Amy on her phone and then vocalizing the animated version of the maggot infested pigs Jake’s dad had to slaughter potentially the one running the show?

If Plemons takes on the energy Kaufman used Philip Seymour Hoffman to conjure in his debut, his performance as Jake turns from an obnoxious boyfriend oblivious to his girlfriend’s shrinking away from him, to a sympathetic victim of his environment. Toni Collette and David Thewlis (who voiced the lead character in Anomalisa) are both entertaining in their troubling formulations of age and awareness, the former’s frantic performance recalling the queasiness of Ari Aster’s Hereditary (2018). Cultural interpretations and fluctuating intentions are also part of this formulation, such as an argument over the meaning of the song “Baby, It’s Cold Outside,” meant as an innocent jingle in 1944 re-interpreted as a song of coercion, potentially date-rape, at the very least, a song about a man dominating a woman because he desires her.

But the hints about Jake’s obsession with musical theater, his sensitivity about homophobic critiques (like Lucy quoting a famous Bette Davis line utilizing the word sissy), Thewlis reducing Billy Crystal as a “nancy boy,” all tied up in the most terrifying use of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma! conjures the portrait of lives not lived, loves unfulfilled, and perspectives constantly thwarted because no one can properly communicate. There’s the life we live and the projected fantasy version of it in our mind’s eye (not to mention media representation, here also displayed by a funny aside involving a standard happy ending rom com directed by Robert Zemeckis), and the nagging thought that perhaps none of our ideas, opinions or understandings are our own.

Paired with the chilly photography of Lukasz Zal (Ida, Cold War, Dovlatov), this is Kaufman at his most radical, like a science-fiction version of Proust, where A Remembrance of Things Past includes not just the future but the fluctuating parameters of faulty memory and changing opinions influenced by what we think is our life, who we think we love and what we thought we kinda knew. But then, maybe that’s Kaufman doing Vonnegut’s “Who Am I This Time?” Or maybe it’s whatever you want to think it is or isn’t.

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆