Anatomy of a Mime: Ozon Explores the Seduction of Indifference

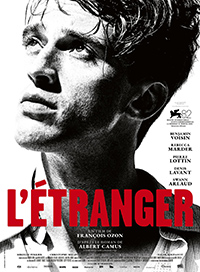

Decades before Hannah Arendt introduced her concept of ‘the banality of evil,’ Albert Camus had already written a template deserving of such distinction with his 1942 novella The Stranger. Previously adapted by Luchino Visconti in 1967 (which also premiered in competition at the Venice Film Festival), François Ozon formulates a more definitive attempt to encapsulate the existential dread and bureaucratic absurdity of the novel. Shot in black and white by cinematographer Manu Dacosse, its elegant starkness blends into a near-constant dread enhanced by Kuwaiti musician Fatima Al Qadiri’s sinister score, made all the more troubling by the serene demeanor of Camus’ infamous emotional void of a protagonist, Meursault.

Decades before Hannah Arendt introduced her concept of ‘the banality of evil,’ Albert Camus had already written a template deserving of such distinction with his 1942 novella The Stranger. Previously adapted by Luchino Visconti in 1967 (which also premiered in competition at the Venice Film Festival), François Ozon formulates a more definitive attempt to encapsulate the existential dread and bureaucratic absurdity of the novel. Shot in black and white by cinematographer Manu Dacosse, its elegant starkness blends into a near-constant dread enhanced by Kuwaiti musician Fatima Al Qadiri’s sinister score, made all the more troubling by the serene demeanor of Camus’ infamous emotional void of a protagonist, Meursault.

In 1930s French Algeria, thirty-year-old Meursault (Benjamin Voison, of Ozon’s Summer of ’85, 2020) lives the life of a humble bachelor, drifting along in his mediocre desk job until he receives news of his elderly mother’s death. While he diligently attends the funeral, he seems relieved at her passing, having shut her up in a rest home years prior. Heading to the beach after the services, he runs into Marie (Rebecca Marder, of Ozon’s The Crime is Mine, 2023), a woman he’d met years prior. It’s clear Marie is attracted to Meursault and he accepts her advances. Back home, he becomes embroiled in the melodrama of his violent neighbor, Raymond (Pierre Lottin, of Ozon’s By the Grace of God, 2018). The brother of his mistress, an Algerian, has been following him, trying to punish him for beating and abusing his sister. While vacationing at a mutual friend’s cabin one Sunday, Meursault murders the Algerian man in cold blood. He’s brought to trial, though can’t quite explain himself, with the prosecuting attorney focusing on Meursault’s indifferent attitude towards his deceased mother.

The dense subtexts and symbolism of Camus’ novella aren’t exactly easily transferable to the screen, which (partially) explains why something like Visconti’s earlier version wasn’t entirely successful (especially compared to Visconti’s accomplished 1971 adaptation of Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice). Marcello Mastroianni as Meursault, for instance, felt too mature for the role, portrayed as a dapper, empty-headed kook who might as well have stepped off the set of Divorce Italian Style (1961). Ozon’s more somber approach could have easily morphed into the portrait of a sociopath, with Meursault translating into a non-entity along the lines of Patricia Highsmith’s Tom Ripley character (though stripped of queer sensibilities, like Alain Delon’s interpretation of Ripley in Rene Clement’s Purple Noon, 1960). Voison, playing the opposite of the ambitious youth in Lost Illusions (2021), feels eerily detached from himself and those around him from the opening frames. Whenever he opens his mouth, only a deepening apathy escapes it.

Ozon opens the film with vintage footage proclaiming how France’s colonization of Algeria basically wrestled the country out of the ignorant dark ages to become a transplanted vestige of their own culture. The violence associated with colonialism is apparent everywhere, characteristics and details all underlining this same purpose to provide the environment which created a personality such as Meursault (whose surname is a play on the words for ‘death’ and ‘sea’ — in other words, a black hole). Denis Lavant appears as a beggarly neighbor who abuses his dog before it runs away. Pierre Lottin is another neighbor who physically abuses his Algerian girlfriend when he’s not pimping her out. These behaviors are normalized, their relations described as an ‘odd couple’ or shrugging off domestic abuse as something that’s simply ‘their business.’ Meursault’s detachment defies behavioral social expectations in almost every regard, including his mother’s funeral or while watching a Fernandel comedy with his girlfriend.

While not exactly a hedonistic, Meursault intently pursues the satisfaction of life’s simpler, leisurely pleasures, constantly smoking, eating at cafes, or having sex with his girlfriend. But even these acts seem perfunctory, interchangeable. The aggravatingly oblivious Marie (played by a wide-eyed Rebecca Marder, whose interpretation of the character is that of a Stepford volunteer), willfully ignores a bounty of red flags. She quickly begins to nag him about marriage, hinting at professing their love for one another. “There’s no point,” he tells her. “Love means nothing.” If not Marie, he’d simply be with the next woman who stakes a claim to him. Since everything is meaningless, nothing matters.

Where the bitter irony of The Stranger arrives is via the trial, highlighting the gross indifference of the actual murder to instead debate the crimes Meursault has committed against cultural expectations. Benefitting from his privileged stance, the world opens up before someone like Meursault without him ever having to really lift a finger. But he refuses to validate the culture that rewards his existence by declining to participate in their expectations. His disdain for his own culture is what’s troubling for the gatekeepers. Jean-Charles Clichet, playing Meursault’s lawyer (and looking somewhat like vintage Vincent Price) argues valiantly that it was the fault of the sun, blinding and confusing his client as he shot an Algerian man to death.

If there’s anything shocking about The Stranger it’s the verdict he receives, but justice for the family of his victim is not the intention. Another Ozon alum, Swann Arlaud, pops up at the finale as an insistent chaplain urging Meursault to repent, and it’s unclear which man seems more trapped by the dogma shackling them. Lifting directly from Camus’ prose in the final throes, Ozon’s take on The Stranger effectively administers the source’s intentions—and clearly, there is a point, even if Meursault himself would reject it. Sadly, amongst it messaging, embracing the idea of ‘the tender indifference of the world’ means one can only depend on the unkindness of strangers.

Reviewed on September 2nd at the 2025 Venice Film Festival (82nd edition) – In Competition. 120 Mins.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆