Indiscretion of an Icelandic Wife: Palmason Primes a Crime of Passion in Simmering Drama

Nothing is initially what it seems in Icelandic director Hlynur Palmason’s striking sophomore film A White, White Day, a brooding, slow burn character study which initially portends to be something akin to a neo-noir. But while it paints a portrait of a grieving man who becomes emotionally unhinged, it’s also a striking, albeit austere portrait of relationships regarding dual perspectives, taken-for-granted notions of desire, personal fulfillment, and ownership of another.

Nothing is initially what it seems in Icelandic director Hlynur Palmason’s striking sophomore film A White, White Day, a brooding, slow burn character study which initially portends to be something akin to a neo-noir. But while it paints a portrait of a grieving man who becomes emotionally unhinged, it’s also a striking, albeit austere portrait of relationships regarding dual perspectives, taken-for-granted notions of desire, personal fulfillment, and ownership of another.

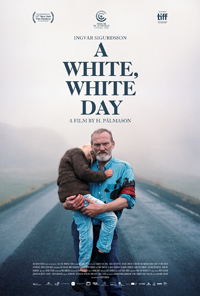

Palmason directs noted actor Ingvar Sigurdsson in one what may be the most ferocious performance of his career as a man chasing ghosts upon realizing a heretofore ignorance about his life and relationships.

Palmason employs his Winters Brothers (2017) DP Maria von Hausswolff to construct a careful layer of framed images which deftly construct the film’s subtexts. Once we realize what the story is and where it’s going, A White, White Day would seem to lose some of its potency as a mystery thriller—but then this elliptical melodrama isn’t actually trying to be encapsulated within the confines of genre, actively eluding exposition as we learn what has happened.

Throughout the film there are various repeated sequences featuring two windows or two distinct perspectives separated by a divide. Both windows or perspectives ostensibly provide the same view of the same landscape, but each one sees the same landscape slightly different—or sees objects or meaning outside the purview of another perspective. The two windows diagram is repeated visually in Ingimundur’s droll exchanges with a therapist, which only highlight his estrangement from his own emotions.

Also, the notion of perspective becomes tantamount in relation to Ingimundur’s discovery of his wife’s secrets through photographs and her recorded footage, further highlighting the different intent and emotion we each bring to any given example—which correlates brilliantly with a cathartic finale in which Ingimundur envisions his dead wife dancing naked as Leonard Cohen’s “Memories” graces the soundtrack—we can only really control our own emotions and memories of another, and as the anonymous quote opening the film suggests, it’s perhaps only a hazy, nebulous frontier with which “the dead can talk to us who are still living.”

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆