Spy Game: Kurosawa Finds Passion & Terror in History’s Gloom

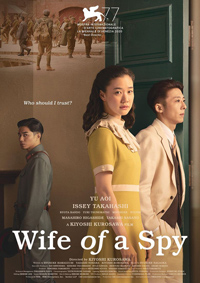

One doesn’t tend to associate period melodrama or espionage with Kiyoshi Kurosawa, a perennial genre auteur who revels in existentialist subtexts. For his first outing in these waters with Wife of a Spy, Kurosawa reveals one of his most invigorating narratives in years, co-written by director Ryusuke Hamaguchi and Tadashi Nohara (Happy Hour, 2015).

One doesn’t tend to associate period melodrama or espionage with Kiyoshi Kurosawa, a perennial genre auteur who revels in existentialist subtexts. For his first outing in these waters with Wife of a Spy, Kurosawa reveals one of his most invigorating narratives in years, co-written by director Ryusuke Hamaguchi and Tadashi Nohara (Happy Hour, 2015).

Tempestuous romance and horrific manipulations gird the sordid historical subtexts of Japan on the eve of entering WWII, presented through the perspective of its most problematic character, an unhappy, headstrong housewife played with resolute naïveté by Yu Aoi. Majestic, and with just the right amount of customary foreboding Kurosawa is known for, this is handsomely attenuated filmmaking straddling the aesthetic of the past with the transparency of the present.

In 1940 Kobe, Japan, Satoko Fukuhara (Yu Aoi) lives a comfortable life with her husband Yusaku (Issey Takahashi), a silk merchant dabbling in filmmaking. Their frivolity is interrupted by the encroaching threat of war, and Yusaku’s vocal opposition isn’t matched by his wife. While away on a business trip to Manchuria, Satoko bamboozles an old flame, Taiji (Masahiro Higashide), who is now the head of the military police, into an intimate drink at her home. Taiji has already had an uncomfortable conversation with Yusaku after deporting a British expat who was a colleague in the silk industry. Yusaku, who returns from his trip with Fumio (Ryota Bando), has brought back a mysterious woman whom he assists in getting a job at a hotel. When she’s found murdered, Satoko begins to suspect her husband of being a traitor. Backing him into a corner, she learns he witnessed colonialist atrocities in Manchuria, with written evidence of experimentations on the populace which resulted in a deadly plague. Satoko takes charge of the scenario which leads to irrevocable collateral damage, but awakens a lust for her marriage she’s likely never felt before. Together with Yusaku, she hatches a plan of defection, her stance against Japan’s militarism more happenstance than anything else.

In a similar vein to something like Lou Ye’s recent Saturday Fiction, mixing period entertainment and espionage, Kurosawa directly references Kenji Mizoguchi, an auteur whose preference for mixing offbeat elements courts comparison to his own filmography. Satoko lies about attending a matinee of a Mizoguchi film (notably, his famed The 47 Ronin premiered days before Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor), and though the film directly positions her in the role of the antagonist, she’s actually the asp neath the flower.

Sacrificing Fumio as a pawn in her own vengeful scheme to reclaim her husband’s attention, she’s like the prized antagonist of those rare women’s pictures of the Hollywood studio era focusing on a woman scorned, her cruelty akin to Bette Davis’ famed sequence in The Little Foxes (1941). What follows is a queasy energy whereby the audience guesses well ahead of Satoko how Yusaku really feels about her actions.

Unfortunately, Kurosawa’s near-perfect pitch ambience is ruined by an exchange in English (think the ruinous energies of such passages in Jia Zhang-ke’s Mountains May Depart or Im Sang-soo’s The Taste of Money), but the sequence is brief enough to sail through to the film’s karmic denouement. Although similar in tone to his enigmatic 2016 French language debut Daguerreotype, Kurosawa reveals new facets with this haltingly lush melodrama of wartime horrors and a woman’s selfishness. Although still best revered for his early horror films, like the tonally formidable Cure (1997) or the well-traveled Pulse (2001), Kurosawa’s infrequent dips into new waters, whether it be to Uzbekistan in To the Ends of the Earth (2019) or the shadows of the past in Wife of a Spy, are always invigorating.

Reviewed on August 27th at the 2021 Japan Cuts – Centerpiece Presentation. 115 Mins

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆