Husband and Wives and Bears, Oh My!: Levine’s Dark Dream an Ambiguous, Playful Psychodrama

The crux of our innate creative necessities might require something beyond the bare, at least as far as the leitmotif suggests in the fourth feature from Lawrence Michael Levine, the perspective changing psychodrama Black Bear. Dedicated to the director’s wife, actor/writer/director Sophia Takal, there’s an authentic, festering aftertaste to the film’s lofty, inconclusive artistic packaging which examines brittle, tenuous relationships floundering beneath the weight of collaborative undertakings.

The crux of our innate creative necessities might require something beyond the bare, at least as far as the leitmotif suggests in the fourth feature from Lawrence Michael Levine, the perspective changing psychodrama Black Bear. Dedicated to the director’s wife, actor/writer/director Sophia Takal, there’s an authentic, festering aftertaste to the film’s lofty, inconclusive artistic packaging which examines brittle, tenuous relationships floundering beneath the weight of collaborative undertakings.

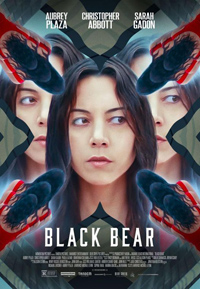

A throwback to both the celebrated theatricality of morbid stage dramas (the bread and butter of Tennessee Williams or Edward Albee) and the abrasive arthouse marital escapades of early Polanski, Levine straddles the venomous sabotage of banal human instincts with the existential fumes of creative flow born from razed ennui. It also provides its lead Aubrey Plaza with the kind of nuanced characterization her own distinct persona often eclipses, and the result is equally dark and dazzling.

Allison (Plaza) is an indie director who treks off to the Adirondacks for a creative retreat in hopes to move beyond her writer’s block. Having segued from a persona known as a ‘difficult’ actress to a ‘feminist’ director, how she defines herself and how others see her begins to fluctuate erratically upon being introduced to her host, Gabe (Christopher Abbott), a handsome out-of-work musician who has moved out of Brooklyn with his dancer wife Blair (Sarah Gadon) to his inherited, isolated property, they hope to make lemons out of lemonade and create a notable retreat for creative types such as Allison. But all is not well between Gabe and Blair, the latter in the second trimester of a pregnancy which has relegated her to bedrest. Picking up on the flirtation between Gabe and their comely, notable guest, Blair’s testiness overshadows a shared dinner, which devolves from a jibe-sharing charade into full blown violence.

As we’re introduced to the first black bear promised by the title, the narrative shifts gears, and suddenly Allison is now an actress married to Gabe, a notable director who is on the last day of shooting his latest film in the same location as the previous segment. But it seems Allison has wheedled her way into the lead role and Gabe has been playing mind games to evoke a more impassioned performance, leading his wife to believe he is sleeping with her co-star Blair. The film-within-a-film is similar to the sentiments of the previous segment, but Allison as the actress throws a wrench in the production when she downs a bottle of whiskey and exhibits the early tremors of a nervous breakdown.

Bookended by Allison, at least as we presume her to be, sitting in the middle of a dock branching off into two dead ends, suggests the twin segments unspooling in Black Bear are figments of her own imagination, configurations of a bitter love triangle extricated from her own professional and romantic experiences. Perhaps she is the actress-turned-director or maybe she’s none of these personas. The chapter segments, beginning with “The Bear in the Road,” the segueing to “The Bear by the Boat House,” before finally looping back to the film’s title, suggests the symbolism of the title (which could also be a playful homonym) is an elliptical exercise. The bear, or our own animalistic human nature (the id, perhaps), creeps closer and closer to the actual personification of Allison, from the road, to the boat house, to her interior which leads to a break in the fourth wall.

The first segment, arguably more mired in arch theatricality, plays like Polanski’s Knife in the Water (1962), a stranger invited into the troubled, seesawing power struggle between a heterosexual couple. It also utilizes the usual energies we’ve become accustomed to with Plaza, here an actor-turned-director who seems to be continually reinventing herself to either acquiesce with the troubled personalities in the room or work in opposition to one or both of them. It’s here where Gadon shines brightest as a woman experiencing a difficult pregnancy in her second trimester who can’t seem to stop replenishing her wine glass. The unifying aspects between this segment and the next is a couple unraveling thanks to their participation in a collaboration (a child, a film) the male seems browbeaten into. The other unifier is booze.

Plaza’s falling apart and pulling herself together again in the film within the film of the boat house sequence is a marvelous bit of acting, a performance which at least bears comparison to Gena Rowlands in classics like A Woman Under the Influence or Opening Night. The manipulation of actresses is also vaguely Polanski-like (i.e., the performance culled from Faye Dunaway in Chinatown, for instance) but altogether Levine seems to be working on the wavelength of Ingmar Bergman-level psychodrama.

Of course, backing up even further, Black Bear is similar to his Always Shine (2016), which Takal directed, not to mention her earlier, personal genre-tinged essay on the toxic overload of jealousy in 2011’s Green. But the broader scale Levine accomplishes here really opens everything up to a disastrous, sinking inevitability with the hustle and bustle of the film crew valiantly juggling the egos of the director and his cast.

DP Robert Leitzell also conjures different visual aesthetics between both segments, but the juxtaposition never feels like an exercise more than it does like a commentary on diametrically opposed identities, male vs. female, actor vs. director, partner vs. plaything. And while the finale of Black Bear might not make anything innately clear, the suggestion is, whether personal or professional, every relationship is a fluctuating struggle to fulfill basic needs and desires while trying to maintain an impossible façade.

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆