Mother Has Arrived: Kawase Returns with Intersecting Drama on Motherhood

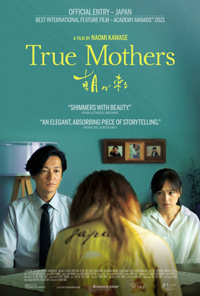

Recently, Naomi Kawase, a staple amongst arthouse enthusiasts of Japanese cinema, has been drifting ever so lightly into the realm of soapy melodrama. Balancing emotional resonance with her formidable aesthetics more effortlessly than evidenced in some of her other comparable forays into this format is True Mothers, an adaptation of a 2015 novel by Mizuki Tsujimura.

Recently, Naomi Kawase, a staple amongst arthouse enthusiasts of Japanese cinema, has been drifting ever so lightly into the realm of soapy melodrama. Balancing emotional resonance with her formidable aesthetics more effortlessly than evidenced in some of her other comparable forays into this format is True Mothers, an adaptation of a 2015 novel by Mizuki Tsujimura.

As is the case across many cultures, the ability and expectation for women to have their own children is a sign of success, a stronghold of familial normalcy. Symbolically, its hierarchical value includes the carrying of the bloodline or the family name and in tangible terms, children are the seeds which will become one’s eventual care provider. Like many conditioned traditions, anything which challenges or subverts the taken-for-granted notion of motherhood tends to stray into the taboo, and such is the crux of the two women at the heart of this tale, a birth mother and an adoptive mother—but not unlike the nature vs. nurture debate, who then is actually the true mother?

When Satoko (Hiromi Nagasaku) receives a call from her son Asato’s school and learns her six-year-old may have pushed a classmate on the playground, she’s intensely bothered by the situation. Her son either cannot remember what happened or is lying about the incident. As this plays out, we backtrack to an earlier point in Satoko’s marriage to Kiyokazu (Arata Iura, of Kore-eda’s Air Doll and Like Father, Like Son) and find due to his aspermia which rendered them an infertile couple, they eventually warmed to adoption upon discovering a non-profit organization called Baby Baton. Eventually, they were assigned Asato, whose teen mother Hikari (Aju Mikita, of Kore-eda’s Shoplifters, After the Storm and The Third Murder) was forced to give him up. Hikari’s ensuing trauma over life at home and the broken romance which caused her pregnancy eventually forces her back to Baby Baton and into the lives of Satoko and Asato.

Over twenty-years into her feature filmmaking career, Kawase, a perennial fixture at the Cannes Film Festival, often delivers narratives a bit ambivalent in comparison to look and tone, her films more often memorable for explorations of feelings and motifs. After 2015’s An (also known as Sweet Bean), Kawase has turned a bit harder into more tactile territories, which also includes 2017’s Radiance, a film which sports its fair share of schmaltz. But with True Mothers, Kawase spins the kind of provocative cultural woes perceived through the individual which aligns it with Hirokazu Kore-eda’s work (and not just because Kawase uses a few of his regular cast members). Divorce seems the immediate probable resolve for marriages where one of the partners suffers from procreative challenges, itself a sly nod to the archaic beliefs which enhances a whole myriad of illogical issues about body functions just as it assists in keeping families who desire having children from ever considering adoption. And at times, True Mothers is a quietly prodding statement about such archaic beliefs amongst a certain traditional segment of Japanese society.

Satoko is often frustratingly passive, twice the target of other women who recognize the potential of mining her obsequiousness for all its worth (and also commentary on the types of schemes made possible by rigid or impossible social standards not everyone can meet). Quickly we learn the events are out of order, which also assists in continuously fluctuating the viewer’s emotions. Satoko’s fretting over whether or not Asato pushed his friend at school ends up with a deeper meaning about her unsaid turmoil (like many adoptive parents) of discovering they may have been saddled with a ‘bad seed.’ But it’s Hikari’s situation which automatically feels more volatile and hopeless, and her sequences amongst the other expecting mothers who will soon be giving up their children at the doomed Baby Baton mines the perspective we don’t often see regarding resentment of those privileged adoptive parents who will whisk away kids when their actual parents are often forced to give up their children due to lack of economic resources.

Neither perspective is black or white, but the variables which define the actions of both sides aren’t often explored with the same bluntness in conjunction. Between these two focal points, True Mothers covers an impressive amount of narrative ground, morphing from social issue film to domestic drama, romantic melodrama, violent urban thriller and at last a quiet reflection of cathartic confrontation. Although themes of adoption have been explored in many films across many countries, Kawase’s compelling addition may be far from the exploitative tendencies of a Losing Isaiah (1995), but isn’t as powerful as the simple but beautiful Adoption (1975) from Marta Meszaros.

Reviewed virtually on September 17th at the 2020 Toronto International Film Festival. Special Presentations Program – 139 Mins

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆