Dance, Fools, Dance: Larraín Dances to Delirium in Arthouse Soap Opera

Pablo Larraín returns to Chile to dance the body electric in Ema, a masquerade of female agency which aligns motherhood with a dangerous passion for pyromania—a duality of creation and destructive forces all wrapped up in one complex woman. Visually a commanding electro-punk dance movie, its supreme stylistic choices overwhelm what amounts to little more than a trashy, sexploitation soap opera. Larraín and his male co-writers never seem to get beyond defining their eponymous heroine beyond her sexual fluidity, crafting a cold, inscrutable portrait of a woman who seems to move in mystery only to reveal questionable choices and desires amounting to nothing more than a pot of nonsense.

Pablo Larraín returns to Chile to dance the body electric in Ema, a masquerade of female agency which aligns motherhood with a dangerous passion for pyromania—a duality of creation and destructive forces all wrapped up in one complex woman. Visually a commanding electro-punk dance movie, its supreme stylistic choices overwhelm what amounts to little more than a trashy, sexploitation soap opera. Larraín and his male co-writers never seem to get beyond defining their eponymous heroine beyond her sexual fluidity, crafting a cold, inscrutable portrait of a woman who seems to move in mystery only to reveal questionable choices and desires amounting to nothing more than a pot of nonsense.

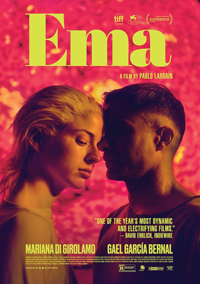

Trapped within its own titillation, the success of the film will depend on audience members being as taken with newcomer Mariana di Girolama as all the supporting characters are in the film, while others may recognize her inscrutable characterization for the empty hull of paradoxical ideas she really is. While it’s a change of pace for Larraín, who after the success of his Pinochet trilogy presented the dark Catholic priest drama 2015’s The Club (review) and then his English debut with the Oscar nominated Jackie (review), this experimental art-house pic written by Alejandro Moreno and Guillermo Calderon needs stronger characterizations to justify the insanity of their commitments and choices.

Ema (Mariana di Girolamo) is part of a modern-dance ensemble in Valparaiso, directed by her husband Gaston (Gael Garcia Bernal, reuniting with Larraín after 2012’s No and 2016’s Neruda). We learn a fiery tragedy involving their adopted son Polo, which maimed Ema’s sister, was cause for him to be taken away from them, debilitating their relationship and affecting her career and creative choices. While, to her husband’s chagrin, she takes to the streets to perform sensuous reggaeton dance numbers with her fellow female troupe members, Ema also concocts a complex plan to reclaim her son Polo.

Her hair shellacked back in a glaring peroxide blonde duck tale, everything about Ema borders on the severe, her sex appeal generating best in her vigorous, lithe dance renditions which work to distract from a plot which remains purposefully vague for success of the inane resolution (which isn’t all that surprising if you’re paying close attention and using deductive reasoning). Never is she shown to be compassionate or loving, while her detachment from the tragedy which resulted in Polo’s departure further alienates the audience from her actions. But Ema is a woman of extremes, and as thus, is a rare, welcome departure from portrayals of women and motherhood we often see. However, her willfulness to seduce everyone in her path becomes a bit obnoxious, especially for those unsold on anything beyond her superficial appeal (considering some of the hyper intelligent women she seduces, all portrayed as neurotics).

Decked out in breakaway Adidas pants and athletic wear, she’s like an androgynous version of old Hollywood starlets, like Joan Blondell and Jean Harlowe—their audience appeal a taken for granted based simply on being presented to us on the big screen. Ema is an idea of what a male writer believes modern female agency looks like, but she is merely a cipher, a representation of ideals defined by and through the utilization of her body—like Aphrodite, designed to be the goddess of Love, sprung from the head of Zeus.

As we begin to puzzle together the events which led to the fiery tragedy of Polo, Ema emerges as the responsible party, a bisexual dance artist with a taste for arson. Paired with her cockamamie plan to reclaim her lost child, it’s questionable whether or not she’s ready for motherhood, which leaves the only sane voice of reason in the film to the agency worker played with flair by Catalina Saavedra (of Sebastian Silva’s The Maid, 2009).

Gael Garcia Bernal is interesting here, looking lost until his blow-up regaling the artistic merits of reggaeton. The real winners, though, are Larraín’s usual DP Sergio Armstrong, who paints a vibrant neon-lit palette—if watched on mute, this could pose as kin to Noe’s Climax (2018). Likewise, Nicholas Jaar’s (Dheepan, 2015) score greatly assists the lethargy of the film, though often in ways which ultimately match up with the style but further alienate from the telenovela plot.

Reviewed on September 8th at the 2019 Toronto International Film Festival – Special Presentations Program. 106 Mins.

★★/☆☆☆☆☆