There’s a Ghost in Me: Zurcher Explores the Necessity of Destruction

Amidst all the existential dread in Franz Kafka’s body of work, silver linings abound, perhaps no more succinctly than in an oft quoted phrase from his diaries, “The relief of giving intro destruction.” In their third feature, the Swiss filmmaking duo Ramon and Silvan Zürcher complete their metaphorical animal themed trilogy with a scream of significant anguish (and relief) with The Sparrow in the Chimney (Der Spatz im Kamin), a culmination of the interconnected miseries and joys wrought through microcosmic communal situations explored previously in 2013’s The Strange Little Cat (review) and 2021’s The Girl and the Spider (review). As in their debut, Ramon Zürcher takes over as director with Silvan producing a similar scenario which feels incredibly intensified by comparison, this time led by one of Germany’s most accomplished contemporary actors, Maren Eggert.

Amidst all the existential dread in Franz Kafka’s body of work, silver linings abound, perhaps no more succinctly than in an oft quoted phrase from his diaries, “The relief of giving intro destruction.” In their third feature, the Swiss filmmaking duo Ramon and Silvan Zürcher complete their metaphorical animal themed trilogy with a scream of significant anguish (and relief) with The Sparrow in the Chimney (Der Spatz im Kamin), a culmination of the interconnected miseries and joys wrought through microcosmic communal situations explored previously in 2013’s The Strange Little Cat (review) and 2021’s The Girl and the Spider (review). As in their debut, Ramon Zürcher takes over as director with Silvan producing a similar scenario which feels incredibly intensified by comparison, this time led by one of Germany’s most accomplished contemporary actors, Maren Eggert.

Karen (Eggert) and her husband Markus (Andreas Döhler) reside in the childhood home she inherited from her parents, surrounded by memories of past turmoil. In the midst of preparing to host an extravagant birthday party for Markus, Karen seems to be more frayed than usual. Prickly interactions, to say the least, define her relationship with her two youngest children, irate teenager Johanna (Lea Zoe Voss), and preadolescent son Leon (Ilia Bultmann). Their eldest daughter Christina (Paula Schindler) fled the family nest some time ago, but slowly makes her way home for the event. Karen’s younger sister Jule (Britta Hammelstein) arrives with her own family in tow, and the siblings couldn’t seem more diametrically opposed. Passive aggressive exchanges abound amidst increasingly troubling character tics from Karen and her formidably unhappy family, and the past comes roaring back to life in an inferno of reckoning.

Wilderness seems to be encroaching upon the frame almost immediately with a cacophony of alarm, a barking dog announcing the approach of intruders. Of course, these interlopers eventually reveal themselves to be family members gathering for a planned celebration, but they arrive with vestiges of the past trespassing dangerously upon intergenerational conflicts. It’s immediately apparent the relationship between Karen and her younger sister Jule (an astutely vulnerable Britta Hammelstein) is incredibly fraught, a dynamic which eventually reveals itself to have originated with the relationship of their parents (something Karen has inexplicably repeated with her own three children, all of whom cannot seem to reconcile extreme disdain for their mother). Much like the monstrous mother from Herve Bazin’s scandalous 1948 autobiographical novel Viper in the Fist (adapted in 2004 by Philippe de Broca with comically inclined Catherine Frot revealing her talents for cruelty), it would appear Karen is a fantastically unhappy woman who’s retreated within herself as a way to cope with past traumas she’s never processed.

Once the gang’s all there, including her eldest estranged daughter Christina (Schindler), who seems guilty of her escape from mother’s clutches, and the mysterious renter/employee Liv (Luise Heyer), who resides in the adjacent cabin which houses the ghostly nexus of the family’s ruination, Zürcher’s maladjusted mess of misery suddenly resembles the heights of Ingmar Bergman’s familial terrors (particularly the cruelty exhibited by Ingrid Thulin and Liv Ullmann in Cries & Whispers, 1972).

Ingeniously bitchy barbs are exchanged between Karen and her middle child, Johanna (Lea Zoe Voss), a young woman whose dreams of a dancer are halted due to a congenital disease. Endless confrontations between the women lead to one disappointment after another for Karen, which culminates in the realization her husband Markus (Döhler) is having an affair with Liv in the same cabin her grandmother used to meet her female lover. Upon Karen’s admission of clinging to the childhood home as a way to stay connected to her mother, a cold, unhappy woman whose marital transgressions led to her husband’s suicide, the ghosts of the past take on visual personifications in Karen’s mind. And it’s here where The Sparrow in the Chimney begins to migrate into a potent, poetically charged metamorphosis.

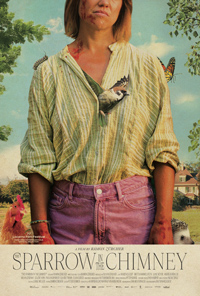

Animals and nature proliferate in the visual and thematic subtexts, suggesting the landscape of the past is itself being eroded and taken over. Karen’s daughters once played on a small island visible from the back of the cabin, now taken over by teeming, squawking cormorants. A decidedly unlucky family cat is murdered by Karen’s beleaguered young son Leon (Ilia Bultmann), a presumed reaction to not only his bullying by a group of local boys but also the lack of affection from his unhappy mother. Karen herself is a literal spider web, butterflies caught in her hair, a situation not to be survived by the metamorphosed insect. In preparation for the celebration, live chickens are beheaded for dinner, one such decapitated fowl landing on Jule as it flops to its death. “That’s what angels look like here,” Karen comments. Much like the titular sparrow caught in the chimney, Karen is a creature trapped in a dangerous place, subject to incineration should she not escape.

As Karen’s conflicts escalate, Eggert’s performance begins to shift from internalized agony to metaphysical self-actualization. This transformation is aided exquisitely by an electro synth soundtrack with several tracks from musical artist Frankumjay and vibrating through increasingly hypnotic visuals from returning DP Alex Hasskerl. A dream of a fiery inferno turns out to be a prescient harbinger to come. And yet, there’s a great relief in what proves to be a relinquishment of the past, a reconciliation through destruction, and the possibility of rebirth.

Reviewed on August 10th, 2024 – at the 77th edition of the Locarno Film Festival – Concorso Internazionale section. 117 Mins.

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆