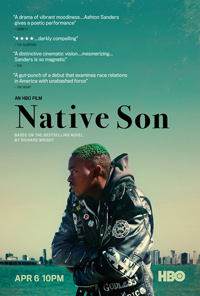

(Not So) Good Times: Johnson Stumbles with Modern Homage to Richard Wright

Marrying historical contexts to modern aesthetics is often an arresting avenue for consideration, and contemporizing Richard Wright’s exceptional 1940 novel Native Son to present-day Chicago is certainly an intriguing if tall order for the directorial debut of Rashid Johnson. Unfortunately, the result misses the mark in a series of anachronistic flourishes by keeping its narrative thrust well within the realm of the novel’s period parameters rather than properly transporting it to terminologies relevant to America’s modern conceptualizations of what being a young black man is stereotyped or perceived as today. Whereas Wright navigated the disparate dualities of the African-American identity, displaying those foregone conclusions and inevitabilities of how black lives were predetermined, limited and deferred by the severe constrictions of white American, Johnson clings to particular facets of the novel which demand to be updated to properly reflect how these systemic conscriptions have mutated into more insidious estimations which birthed more complex systems of degradation and devaluation.

Marrying historical contexts to modern aesthetics is often an arresting avenue for consideration, and contemporizing Richard Wright’s exceptional 1940 novel Native Son to present-day Chicago is certainly an intriguing if tall order for the directorial debut of Rashid Johnson. Unfortunately, the result misses the mark in a series of anachronistic flourishes by keeping its narrative thrust well within the realm of the novel’s period parameters rather than properly transporting it to terminologies relevant to America’s modern conceptualizations of what being a young black man is stereotyped or perceived as today. Whereas Wright navigated the disparate dualities of the African-American identity, displaying those foregone conclusions and inevitabilities of how black lives were predetermined, limited and deferred by the severe constrictions of white American, Johnson clings to particular facets of the novel which demand to be updated to properly reflect how these systemic conscriptions have mutated into more insidious estimations which birthed more complex systems of degradation and devaluation.

Bigger “Big” Thomas (Ashton Sanders) works delivering odd packages as he lives with his mother (Sanaa Lathan) and two younger siblings in Chicago. Aimless and a bit of an outsider, he spends time hanging out with girlfriend Bessie (KiKi Layne) and some of his friends. When his mother begins dating someone new (David Alan Grier), it’s decided Big needs to find better work, and he’s offered a job driving for a wealthy white family. It seems a chance salvation as it allows Big to avoid robbing a local corner store he’d been pressured into agreeing to at the behest of his friends. But working at the Dalton estate immediately puts Big in awkward positions, especially since their comely daughter (Margaret Qualley) seems primed for a variety of indiscretions and illegal activities.

Ashton Sanders manages to be a compelling center to this updated version of Native Son, presented as a social misfit who eschews the cultural markers of his peers by sporting green hair and painted nails whilst listening to metal and classical music. The poverty-stricken family of Wright’s novel appears more comfortably middle-class, Sanaa Lathan working as a paralegal who might pursue law school, widowed by her accountant husband and currently dating a non-profit lawyer (an underutilized David Alan Grier). In the unveiling of Big’s background, we learn little of his desires or dreams, working as a makeshift delivery boy for an unseen boss. His friends are defined by even more anachronistic occupations, such as Aaron Moten’s Tony, working his way up the ranks in a theater house which shows blaxploitation films. When the opportunity is presented to work as a driver, filling a position last occupied by the same man for twenty years (Stephen McKinley Henderson, who looks well into retirement age but we’re told went to business school as the reason for his resignation), it’s unclear how this is supposed to elevate Big in the eyes of his loved ones—yet while it reeks of all the datedness of a Green Book, we can’t forget this is the same glamorous dynamic we’re fed of white, wealthy employers and their black personal aides on a regular contemporary basis (such as the current The Upside, for instance). And so, Johnson does tap into some topical tensions.

But once we get into the sprawling mansion of the Dalton’s, Native Son takes a turn into pseudo genre flair, edged meticulously by Kyle Dixon and Michael Stein’s score. Decorated by an abundance of African-American art pieces, including the visage of Malcolm X, Johnson conjures the unease of Get Out (2017)—where are the influences which would explain this home design? And then there are a series of other alarming misnomers, such as New German Wave star Barbara Sukowa as the live-in maid Peggy, Bill Camp as genuinely affable one-percenter and a creepy Elizabeth Marvel as a blind, overcompensatingly sweet wife. These people must want more than what they’re saying, right? Margaret Qualley (who’s unbalanced persona recalls Isabelle Adjani) gets the brunt of Suzan-Lori Parks’ not-so-subtle racial disparity dialogue, which veers from relevant to caricature and camp, especially when an ill-cast Nick Robinson joins the film as a supposed radical rabble-rouser who wasn’t given any material to really prove this.

There’s an odd, disjointed energy to Johnson’s Native Son, which sometimes, ever so briefly, works towards unnerving us into a sense of the unpredictable. However, an ungainly third act positions Big as a sociopath rather than a black man trapped by the proscribed social conditions of white America, and paints KiKi Layne as merely a passive player in her own relationship, forced to say things like “They broke the mold when they made Big.” Not unlike Christian Petzold’s Transit (2018), which adapted a 1940s novel on post-WWII France by setting it in modern day but utilizing the same methods of communication and transportation as its original source, Rashid Johnson consciously adopts similar methods of solecism. But the inability for this version of Native Son to properly engage with what’s going on and focusing instead, like some dreaded parallel universe, on how things used to be, rides a dangerous line of allowing Bigger Thomas to be defined as an instigator of his own demise, conveniently allowing the social constructions which have created and steered him to wash their hands of any guilt or responsibility.

Reviewed on January 24th at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival – U.S. Dramatic Competition. 108 Minutes

★★/☆☆☆☆☆