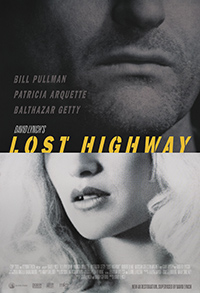

Fugue De Chao: Lynch Hits the Yellow Bricks in Masterful, Neglected Daymare

“I like to remember things my own way,” remarks the onerous protagonist of David Lynch’s neglected 1997 neo-noir, Lost Highway. Memories, of course, are often faulty recollections, the DNA of their missing strands filled in conveniently by our errant data supplied through our mind’s insistence on either restructuring comprehension when something doesn’t make sense or redefining trauma for palatability, recuperation, etc. And while it’s a statement which provides at least a partial key to approaching this dark odyssey, witnesses to this customarily wonky and frighteningly indiscernible landscape are mere subjects to its protagonist’s ordeals in a world where reality and nightmare have fused and then fractured. An analogue prologue to the triptych of films which would signify Los Angeles as the noir counterpart to Oz, continued in the more renowned Mulholland Drive (2001) and the digital hallucinations of Inland Empire (2006), it’s time to reclaim the shackled ellipsis of this confounding but psychologically analytical film from the master of the cinematically inscrutable.

“I like to remember things my own way,” remarks the onerous protagonist of David Lynch’s neglected 1997 neo-noir, Lost Highway. Memories, of course, are often faulty recollections, the DNA of their missing strands filled in conveniently by our errant data supplied through our mind’s insistence on either restructuring comprehension when something doesn’t make sense or redefining trauma for palatability, recuperation, etc. And while it’s a statement which provides at least a partial key to approaching this dark odyssey, witnesses to this customarily wonky and frighteningly indiscernible landscape are mere subjects to its protagonist’s ordeals in a world where reality and nightmare have fused and then fractured. An analogue prologue to the triptych of films which would signify Los Angeles as the noir counterpart to Oz, continued in the more renowned Mulholland Drive (2001) and the digital hallucinations of Inland Empire (2006), it’s time to reclaim the shackled ellipsis of this confounding but psychologically analytical film from the master of the cinematically inscrutable.

Frank Madison (Bill Pullman), a bored tenor sax player living in the Hollywood Hills, receives a strange message over his intercom one day, a gruff voice announcing “Dick Laurent is dead.” Suddenly he finds himself in a terrifying scenario when mysterious VHS tapes start popping up on the doorstep, suggesting someone is watching him and his wife Renee (Patrica Arquette). As the tapes eventually reveal an intruder in their home, they call the police, who aren’t able to provide much assistance. Upon attending a swank party, where Renee mingles with a smarmy cohort from her past named Andy (Michael Massee), Frank is approached by a garishly sinister man (Robert Blake) who claims to know him. The man insists he’s simultaneously inside Frank’s house, verified with a phone call. Rushing home, Frank sees signs of an intruder, but cannot find the man. Meanwhile, Frank’s nightmares about Renee being a woman who isn’t his wife segues into his receiving a tape showing he’s dismembered her body, a crime for which he’s arrested and quickly convicted of. But while in prison, a strange transition occurs and Frank has turned into a missing young man named Pete Dayton (Balthazar Getty), an auto mechanic who lives with his parents (Gary Busey, Lucy Butler).

Released from the prison cell, Pete returns to work where his boss (Richard Pryor), his girlfriend (Natasha Gregson Wagner) and his group of friends (led by Giovanni Ribisi) celebrate his return but are unable to answer any questions about what happened to him. At work, Pete is visited by the sinister Mr. Eddy (Robert Loggia), a powerful criminal under lord who likes the younger man. When Mr. Eddy brings his Cadillac in for service, with his beautiful moll Alice Wakefield (also Arquette) in tow, Pete is smitten, and allows himself to be drawn into a love affair with the woman. Alice, convinced Mr. Eddy knows of their affair, and confirming he’s forced her to act in the pornaographic films he directs under the name Dick Laurent, suggests they rob one of Mr. Eddy’s colleagues, Andy (also Massee). After receiving a thinly veiled threat from Mr. Eddye via a mystery man (also Blake), Pete agrees. But when Andy is accidentally killed, the two of them set off for the sinister cabin owned by the mystery man, leading to events where Pete once again becomes Frank.

Lynch himself described Lost Highway as a psychogenic fugue, a psychological term suggesting a striking divorce from one state of mind only return to it. Also likened to a veritable Mobius strip of a narrative, it’s perhaps a bit too pat to approach (or reduce) the narrative as being a mere psychotic breakdown of Bill Pullman’s Frank Madison, a tenor sax player who has ninety problems, and a mysterious woman is certainly one of them. In the wake of Alexandre O. Philipp’s recent Lynch/Oz (2022) documentary, which examines the director’s filmography as constantly referential to Victor Fleming’s 1939 film The Wizard of Oz (in which Lost Highway pops up more as a footnote), this texts suggests Frank seems to take the place of Dorothy Gale as a human integrating facets of troubled reality with an increasingly complex nightmare.

When Frank (a surname which means ‘freedom’) segues into Pete Dayton (with Lynch ironically casting a Getty as a working class Joe), the characters begin to take on other pertinent signifiers. If Frank’s world is Neo-Noir, his escapism into Pete (i.e., Peter Pan, a lost boy) Dayton (a day time person) is pure, hardboiled noir, where Alice (Alice in Wonderland) Wakefield (suggesting both ‘awake’ and ‘minefield’) is an ice blonde femme fatale hellbent on leading him astray (think Too Late for Tears, The Hot Spot, and countless other noir classics). The femme doubling of Renee/Alice, marked by their change in style (the former is Bettie Page, the latter Veronica Lake) also suggests a collusion with Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958), where a heroic male is drawn into an insidious web solely due to his medical condition (in this case, Frank’s fugue tendencies, where trauma re-inserts him in the film’s finale). The severity of Arquette’s ravishing hairpieces also suggest a slew of visual references from the annals of 1940s horror and noir, like the cult acolyte played by Jean Brooks in Val Lewton’s The Seventh Victim (1943). Visually, Lynch aligns Alice with a black widow spider, while Pete is a moth driving itself towards the death in her blonde heat trap.

Written alongside Barry Gifford, whose novel Wild at Heart was adapted by Lynch in 1990, exemplifying more obvious entanglements with Oz, they’ve created another sinister road movie of intersections and parallels. Much like the road map of sorts represented in the opening credits, we’re traveling down the middle of the highway going nowhere, returning to where we began. A customarily eerie score from Lynch musical muse Angelo Badalementi, aided by Barry Adamson and Trent Reznor, assists in muddling the narrative’s timeframe, especially paired with Lynch’s selection of period specific artists/tracks from Billy Corrigan, Rammstein, and Marilyn Manson, whose cover of I Put a Spell on You plays even more eerily in retrospect as it’s underlining Alice’s striptease at gunpoint to Loggia’s malevolent porn director, Dick Laurent. Increasingly, as we learn, Alice is hardly the damsel in distress, a sister spirit to the troubled Laura Palmer of Twin Peaks.

Besides Manson, the other glaring sore point of Lost Highway is Robert Blake in (what stands to date as) his final film role, forever defined by the mysterious murder of his second wife, Bonnie Lee Bakley (acquitted in 2001, he was found liable for her death in a 2005 Califronia civil court case). As the terrifying Mystery Man, on hand solely to lodge like a piece of glass in your primordial subconscious, his presence as a Lynchian boogeyman is the film’s enduring visage. Like the pancake layered Bette Davis in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962), Blake recreated a sense of (short lived) visual iconicity, eclipsing even an energetic Robert Loggia (here displayed in Dennis Hopper Blue Velvet mode, a role he purportedly vied for).

Loggia is used quite effectively, although a bit hysterically in his tirade against tailgating with one unfortunate victim of road rage, but this notion is paralleled beautifully when Mr. Eddy sics the Mystery Man on Pete (upset that the young mechanic is pulling up a bit too close to another kind of bumper). Los Angeles, natch, is an omnipotent character itself. From the isolated mansion of Frank and Renee, located near the Griffith Observatory, where they are being ‘observed,’ (not terribly unlike the cursed couple played by Juliette Binoche and Daniel Auteuil in Haneke’s 2005 title Cache), to the merely referential Garland Ave. (an homage to Judy Garland rather than a significant street located in L.A.’s Westside). The Starlight on Sycamore instead reflects the fecundity of Raymond Chandler’s Hollywood as the den of iniquity Alice has become a toxic fixture of.

A host of notables are mere figments in service to the story, from Natasha Gregson Wagner’s jilted girlfriend, a doting Gary Busey as an understanding father, a surly prison guard played by Henry Rollins, and the amusing fellow mechanics played by Lynch regular Jack Nance and Richard Pryor, in his final film role. Justifiably off-putting in its simple but nonetheless jarring narrative disorientation, Lost Highway is hardly the empty, superficial exercise it was written off as. Look no further than the magically transfixing slo-mo of Patricia Arquette set to Lou Reed crooning This Magic Moment, the light flickering on her beauty as lust burns deep in Balthazar Getty’s eyes—-it’s a preview of the formidable collaboration of DP Peter Deming and Lynch before the extravaganzas of Mulholland Drive and “Twin Peaks: The Return” (2017). We’re all on a road hurtling us inevitably forward, and even if our mind skitters sideways, we’re all on a fixed destination to degradation.

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆