Pigments of Your Imagination: Inside Van Gogh’s Mind

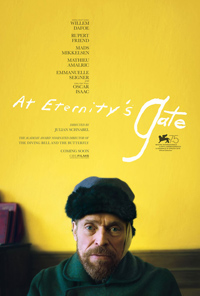

Julian Schnabel’s aesthetically-spellbinding Vincent Van Gogh biopic, At Eternity’s Gate, places viewers inside the Dutch artist’s eye. Rich in color and texture, daubed with thick brushstrokes that leap off the screen, this film is a work of art. Schabel goes to great length to communicate—as Van Gogh himself did—in the language of painting. At times, abstraction trumps dramatic tension, but mesmerizing camerawork, resplendent Van Gogh-esque compositions and an agonized performance by Willem Dafoe keep us immersed. It’s a beautifully odd, oddly beautiful, haunting fever dream of a film—and a worthy portrait of the late painter.

Julian Schnabel’s aesthetically-spellbinding Vincent Van Gogh biopic, At Eternity’s Gate, places viewers inside the Dutch artist’s eye. Rich in color and texture, daubed with thick brushstrokes that leap off the screen, this film is a work of art. Schabel goes to great length to communicate—as Van Gogh himself did—in the language of painting. At times, abstraction trumps dramatic tension, but mesmerizing camerawork, resplendent Van Gogh-esque compositions and an agonized performance by Willem Dafoe keep us immersed. It’s a beautifully odd, oddly beautiful, haunting fever dream of a film—and a worthy portrait of the late painter.

In the film’s opening, Van Gogh asks a young lady permission to sketch her; she shoots back, “Mais, pour quoi?” [But, why?] At Eternity’s Gate spends its duration answering this question. Most viewers will already know the main story beats: Van Gogh, the quintessential tormented artist, travels to Arles, France, chasing sunlight. He may lack communication skills, but he sure paints a mean landscape. For him, painting is an addiction—and a release from his increasingly addled psyche. And, of course, there’s the part with the ear. Schnabel and co-writer Jean-Claude Carrière wisely avoid traditional scripting in favor of a meditative character study, where Van Gogh’s art—and the film’s artistic language—is more indicative of his character than any mere dialogue.

The film rebels against visual standards as well. The handheld camera swivels and sways like a rocking ship. Exquisitely composed frames self-destruct. Van Gogh’s tortured mind gives us dizzying POV shots; abrupt black-screen stoppages; designed-to-shock jump-cuts; a crescendo of split diopters; enough lens flares to thrill JJ Abrams. Plus an audio-visual overlay stacked onscreen like pancakes. At times, it feels almost overloaded—but it’s hard to fault Schnabel for his unapologetic commitment to artistic fervor. Art on the thin edge of madness.

Dafoe channels Van Gogh with perfervid nervous energy, bridging the gap between insanity and relatability. We understand why people see him as a freak, and sympathize more deeply because of it. It’s Dafoe’s film, but there are other key players: Oscar Isaac as Paul Gauguin, Vincent’s persnickety, fair-weather friend; Rupert Friend as Théo Van Gogh, Vincent’s beloved brother and lone emotional ally; Mads Mikkelsen as the priest whose disdain for Van Gogh’s artistic style outweighs his concerns for Vincent’s health.

The film’s most significant supporting protagonist, however, is the natural landscape of Arles – and, later, Auvers-sur-Oise. Benoît Delhomme’s camera captures the texture of light hitting leaves in the late afternoon with the sensuous intensity of a Van Gogh painting. Vibrant yellows, oranges, greens and blues dance across the screen. In these moments, we truly feel like we’re seeing the world from the artist’s perspective. Coupled with an appropriately unpolished, manic piano score, watching Dafoe paint is undeniably convincing—and cool.

The film’s title holds a bittersweet duality: on the one hand, it suggests that Van Gogh’s attempts to express nature on canvas were his form of grasping at eternity; on the other, it also hints at the artist’s premature death and his race to the finish—eternalizing his work before the Gate closed behind him. In fact, to continue the metaphor, Schnabel and Dafoe portray Van Gogh as a Christ-like figure (no coincidence that Dafoe played the Son of God in the The Last Temptation of Christ); but it’s Van Gogh’s human side—passionate, troubled, and desperately misunderstood—that remains with us after the credits roll. This is especially evident in the pure, delicate love between the brothers, Vincent and Théo—a rare thing even today, and (unfortunately) one of the film’s most underused elements.

According to the film, “a grain of madness makes for the best art.” And not just for Van Gogh: At Eternity’s Gate imbues even the least talented among us with the urge to paint, to draw, to create, to embrace nature and reach for the infinite … even if it’s just beyond our grasp.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Reviewed on October 12th at the 2018 New York Film Festival – 110 Minutes