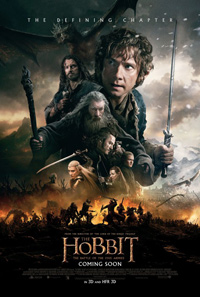

An Expected Finale: Jackson Brings Tolkien Saga to Thankful End

Upon reaching the end of Peter Jackson’s Hobbit trilogy with the third and final installment, renamed The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies, those familiar with J.R.R Tolkien’s novel that preceded the opus of the Fellowship trilogy should pause momentarily to realize that these three films have moved well beyond the spirit or intentions of the source material. A narrative strained beyond the limit, even for Jackson’s taxing penchant for extended, operatic battle sequences, this final offering may deliver on the promise of its title, but beyond a bloated, mind-numbing free-for-all that feels like watching a bunch of school kids playing Dodge ball with reckless abandon, Jackson fails to instill the same sense of awe and magic evident in his first round of monolithic films over a decade ago.

Upon reaching the end of Peter Jackson’s Hobbit trilogy with the third and final installment, renamed The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies, those familiar with J.R.R Tolkien’s novel that preceded the opus of the Fellowship trilogy should pause momentarily to realize that these three films have moved well beyond the spirit or intentions of the source material. A narrative strained beyond the limit, even for Jackson’s taxing penchant for extended, operatic battle sequences, this final offering may deliver on the promise of its title, but beyond a bloated, mind-numbing free-for-all that feels like watching a bunch of school kids playing Dodge ball with reckless abandon, Jackson fails to instill the same sense of awe and magic evident in his first round of monolithic films over a decade ago.

With the irksome dragon Smaug dispatched early on, the cavernous mountain of jewels he’d been endlessly napping upon are seized by the dwarf king Thorin (Richard Armitrage). Rather than honor his promise to share the riches with the humans whose township was laid to waste by the dragon’s flames, Thorin decides to keep all the jewels to himself, as well as the elven heirlooms that Thranduil (Lee Pace) is eager to reclaim. It seems Smaug marinated these trinkets with his noxious attitude, which has infected the simpleminded dwarf king. As Gandalf (Ian McKellan), Galadriel (Cate Blanchett), and Saruman (Christopher Lee) face off in a windstorm of sticks and curses against the dark presence seeking to take over, Thranduil and the humans led by Bard (Luke Evans) seek to take their share of the treasures by force. Thorin’s cousin arrives with his own army, but all are intercepted by the army of Orcs that are regurgitated from the bowels of the earth to wreak havoc on all. Meanwhile, Bilbo (Martin Freeman) is caught somewhere in the middle of all this warmongering and Legolas (Orlando Bloom) and Tauriel (Evangeline Lilly) show up to voice their progressive ideas about unity.

If the abysmal first portion of this endeavor, An Unexpected Journey, felt like an excruciating fan-boy dinner party and the much improved second chapter, The Desolation of Smaug a tastier morsel of promising foreboding, the grand finale lands somewhere in the middle, as it’s difficult to ascertain the merits of a film locked almost entirely in either battle or opposing face-offs and retaliatory based conversation. One wishes that Jackson had the ability to edit himself and had eschewed the greedy profit-based filmmaking model for studio franchising. The Hobbit would have been successful as one, epic film instead of three different films all operating on extended narrative plateaus, and Jackson could have combined elements of all three and still retained his bombastic vision of Tolkien’s material.

For those not in awe of Jackson’s overdone battle sequences, where it seems the goal was only to have something swirling about on screen no matter what the narrative cost, The Battle of Five Armies is merely the inevitable end to a series of films that the filmmaker can finally lay to rest so that he may hopefully pursue material that will continue to challenge. Yes, there are first rate special effects to be experienced throughout this final film, but they’ve paled in comparison to their own feats, and there’s still a nagging sense of watching endlessly manipulated imagery that tends to make attention wane. CGI is a bane to many an auteur’s visual acuity, and Jackson’s films, like later Tim Burton, are on autopilot. Cheap humor and broad characterizations are flung into the mix, with much of the usual overly dramatic language unable to disappear behind the nifty visuals as easily as when this all seemed first rate.

Since it’s the last part of the prequel leading up to a tale fans are already familiar with, there’s little by way of surprise—we already know the extent of everyone’s powers. Blanchett’s Galadriel gets another green tinted freak out session that’s similar to one we see in Fellowship, and McKellan’s Gandalf is a constant, steadfast strength. Richard Armitage’s Thorin is the only character that undergoes any kind of transformation, and Fran Walsh and Philippa Boyens’ screenplay is apparently satisfied with showing base human emotions in a series of extremes. Those notoriously bitchy elves are ever haughty here, but the forbidden love that blooms between Evangeline Lilly’s elf and Aidan Turner’s dwarf ends in a laughable exchange. “If this is love, take it from me,” she sobs. “Why does it have to hurt so?” To which Lee Pace’s Thrandruil replies, “Because it was real.” Interesting, considering nothing else in this bloated triptych seems satisfied with anything as monumentally banal as reality.

★★½/☆☆☆☆☆