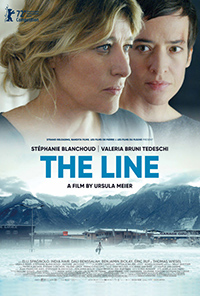

Fists Out of Pocket: Meier Mines Superficial Dysfunction with Uneven Comic Melodrama

Although she’s been working on a variety of documentary and short projects, not to mention a compelling segment of the 2018 Shock Waves television series Diary of My Mind (read review), it’s been a decade since Ursula Meier’s last narrative feature and she returns with another dollop of idiosyncratic familial dysfunction with La ligne (The Line). Once again showcasing new faces against renowned cast members, there’s much to admire on the surface in this latest offering of one family’s specific woes. But the narrative drives into immediate high gear and unfortunately stays completely on the surface as we navigate a traumatic situation involving one fragile yet imperious mother and her detached affect towards her three daughters. Despite some committed performances and interesting character tics, the necessary glue binding these personalities together never sets properly, making it more of a soap opera than symphony.

Although she’s been working on a variety of documentary and short projects, not to mention a compelling segment of the 2018 Shock Waves television series Diary of My Mind (read review), it’s been a decade since Ursula Meier’s last narrative feature and she returns with another dollop of idiosyncratic familial dysfunction with La ligne (The Line). Once again showcasing new faces against renowned cast members, there’s much to admire on the surface in this latest offering of one family’s specific woes. But the narrative drives into immediate high gear and unfortunately stays completely on the surface as we navigate a traumatic situation involving one fragile yet imperious mother and her detached affect towards her three daughters. Despite some committed performances and interesting character tics, the necessary glue binding these personalities together never sets properly, making it more of a soap opera than symphony.

After violently assaulting her mother Chrstine (Valeria Bruni Tedeschi) at a family gathering, rendering her deaf in one ear, thirtysomething Margaret (Stephanie Blanchoud) is placed on a ninety day restraining order from her family, forbidden from coming within 100 meters of the family home. Thrown into couch surfing with her grouchy ex-boyfriend/musical partner (Benjamin Biolay), Margaret’s agitation only intensifies, her need to be home stronger than ever. Quickly we learn she has a significant history of violence, and her mother’s behavior towards Margaret and her two other daughters, the pregnant Louise (India Hair) and twelve-year-old Marion (Elli Spagnolo), confirms a history of dysfunctional attachment styles. Marion takes it upon herself to paint a boundary marking 100 meters from the house, and each day Margaret meets her at the edge of the line to provide music lessons for Marion. Discovering Christine’s resentment for Margaret goes back to giving up her professional career as a musician makes the current situation all the more symbolic, driving Christine from the arms of current husband Serge (Eric Ruf) to a new, younger lover, Herve (Dali Benssalah). As the restraining order comes to an end, Christine must finally face Margaret for the benefit of them both.

A striking, if somewhat overzealous opening sequence showcases a ferocious face-off between Margaret and Christina, so vicious in it’s slow-motion unveiling it plays like beautifully choreographed, violent ballet. But Meier never comes near the same intensity once exposition is lazily applied. Telling rather than showing, Tedeschi’s forced dialogue with youngest daughter Marion informs us of the brooding resentment she’s always had for her eldest daughter, ruining her professional aspirations as a piano soloist, and now, by making her deaf in one ear, robbing the last vestiges of her greatest passion.

Tedeschi is entertaining, but plays this character to the hilt, approaching Christina in the vein of ‘Faye Dunaway IS Joan Crawford’ territory, but her energies are at odds with the rather earnest despair of Stephanie Blanchoud, who carries an intensity similar to wounded women often played by Hilary Swank. The extreme tonal shifts from comedy to melodrama could work if the film had properly oriented us within this family’s dynamics, drawing from the juxtaposed energy of these two women, but the result of their dynamic refuses to coalesce within the limited parameters of the script.

Caught between these power sources are the two other sisters, the kindly Louise, played adeptly by India Hair and the preadolescent Marion, with Ellie Spagnolo left to define her character solely through religious predilections. Margaret’s tangential relationship to her ex, played by Benjamin Biolay, who’s basically utilized as stern convenience, feels tacked on, as does her own troubled musical career.

A looming come-back concert for Margaret seems at odds with her extreme issues with anger management, and like the impetus for the film’s opening melee, demands a better explanation than the ambivalence afforded here. As it stands, Margaret’s compulsions play like the adult version of the child from Nora Fingschedit’s System Crasher (2019). The metaphor of boundaries being crossed eventually swallows the narrative with its thin blue line literally painted in the sand, while significant trauma and ingrained dysfunction feel like window dressing for a more compelling approach. Too conveniently assembled to really address the messiness of the situation, The Line feels like a far cry from the stark cruelties of Sister (2012) or the troubling scenario of Meier’s 2008 debut Home, which felt akin to Haneke’s The Seventh Continent (1989). For fans of Tedeschi on overdrive (a la Paolo Virzi’s Like Crazy, 2018), there’s certainly fun to be had, but the catharsis the narrative aims for remains far out of its reach.

Reviewed on February 12th at the 2022 Berlin International Film Festival – Competition Section. 101 mins.

★★/☆☆☆☆☆