Do You Know Where You’re Going To?: Chou Explores Identity & Adoption Through Complex Character Portrait

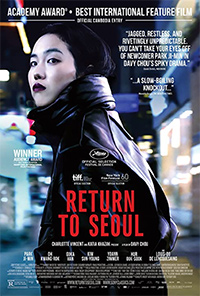

Davy Chou returns with an intimate, unpredictable portrait of an intimate scenario in his sophomore narrative feature, Return to Seoul. The original French language title feels a bit too literal, while its poetic former English language title, All the People I’ll Never Be feels a bit too ambiguous in relation to the emotional journey and superb interiority displayed by its protagonist. Spanning eight years in the life of a young woman born in South Korea and adopted by French parents, an unplanned trip to her birth country at the age of twenty-five creates a ripple effect spanning into her early thirties. Newcomer Park Ji-Min embodies an impressive range of emotional nuance, captivating even when Chou’s film takes drastic turns in tone as he demarcates three separate periods in her life.

Davy Chou returns with an intimate, unpredictable portrait of an intimate scenario in his sophomore narrative feature, Return to Seoul. The original French language title feels a bit too literal, while its poetic former English language title, All the People I’ll Never Be feels a bit too ambiguous in relation to the emotional journey and superb interiority displayed by its protagonist. Spanning eight years in the life of a young woman born in South Korea and adopted by French parents, an unplanned trip to her birth country at the age of twenty-five creates a ripple effect spanning into her early thirties. Newcomer Park Ji-Min embodies an impressive range of emotional nuance, captivating even when Chou’s film takes drastic turns in tone as he demarcates three separate periods in her life.

Freddie (Park Ji-Min) finds herself in Seoul at the age of twenty-five by peculiar circumstance, literally blown in by the wind by a sort of fate. She immediately befriends Tena (Guka Han), a serene young woman working the check in counter at Freddie’s hotel who is surprised to learn the visitor is French, a language she also fluently speaks. While out for drinks, Freddie reveals she was born in South Korea and adopted as an infant, never having met her biological parents, nor did she specifically have a mind to. But when she’s told about the Hammond Adoption Center, she visits with what little information she has, and within a few moments, her file is discovered. Opting to have the agency send both her bio parents telegrams, her father (Oh Kwang-Rok) immediately responds, and she drags Tena along with her to Gunsan to act as her interpreter. There she also meets an aunt and grandmother, but was not expecting such an extreme outpouring of emotion from her father, who texts and calls incessantly, often when drunk and crying.

When Freddie expresses dismay about her father pouring out his sorrow on her, Tena tells her “It’s the way of Korean men.” As her two weeks comes to an end, Freddie becomes desperate to hear from her biological mother, who never responds. Then, the film shifts two years into the future, where Freddie has relocated to Seoul and meets a French weapons dealer (Louis-Do de Lencquesaing), who will come in handy. With no word from her mother, another five years passes, and now thirty-two, Freddie appears to have some financial and emotional stability, happily dating Maxime (Yoann Zimmer), who tags along on a lunch date with her aunt and father. But something sours her on Maxime, and going off on a bender that night, she wakes the next day alone in an alley. However, her mother has finally responded to an agency telegram—-a meeting is established, tears are exchanged, and her mother gives Freddie an email address. Another year passes, and Freddie finds herself alone on a pilgrimage where she’ll receive one final disappointment.

Both Park Ji-Min and the film itself tend to operate on their own specific vibration. An enticing score from his Diamond Island composers Christophe Musset and Jeremie Arcache, plus a well-curated soundtrack selection of moody Korean and vintage pop rock assist in creating an electric vibe, granting Freddie her own theme which promises to bleed into Bauhaus’ classic “Bela Lugosi’s Dead.”

What attracts people to Freddie sometimes eventually repels them, and the more we get to know her, we realize she’s testing people as well. Attracting a certain mystery which often lends itself to chaos, she seems intent on setting fire to whatever comfort she’s created for herself, reinventing a different version she likes better. Tapping into notions of not belonging, displaced from one’s culture and forever foreign to various host cultures, she’s searching for a semblance of completeness, what is often described as the sense of home.

At the end of the first sequence, where she demeans a Korean boy she slept with, as well as newfound friend Tena, Freddie takes to the dance floor at the bar they’re in and dances her heart out—it’s a spectacle akin to the first introduction of Andrew Garfield in Boy A (2007), where dancing and music provide a catharsis language simply cannot. Early on, Freddie introduces the concept of sight recording, a term used in music as an ability to detect notes ahead of time—and music plays an important role in Freddie’s development. When her biological father plays instrumental music he wrote for her, Chou shows the seconds remaining on the track, in turn signaling Freddie’s immediate abandonment of Maxime following a pleasant but emotionally potent dinner with her father and aunt. The film’s most cathartic moment at the Hammond agency arrives quite late, and Chou keeps the camera in close-up on Freddie’s profile. What’s most astute about this moment and others allowing for a rendering of poignancy is how they also suggest an incompleteness—-as in life, they are moments, not cure alls.

There’s a sense of disjointedness to Return to Seoul which may seem discordant as far as the film’s rhythm but hews close to how transitions in life occur, where growth and maturity lead to understanding, sometimes peace, without respect to finesse. At each juncture in the film, an emotionally disruptive event occurs, a pattern apparent into the bitter end where one final major disappointment threatens to agitate. And while the specifics of adoptee experience (strikingly significant for Korean children adopted by French parents), the significance Freddie embodies is the bittersweet reward of how an angry, despairing search for the self reveals itself to be the constant we must learn to enjoy and embrace. We’re left with a sense of finality and acceptance, with Freddie crafting her own gentle tune, providing the audience with a sort of sight reading of what’s to come in her next steps.

Reviewed on May 22nd at the 2022 Cannes Film Festival Un Certain Regard. 116 Mins

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆