Wild at Heart: Serebrennikov Oversimplifies Odyssey of Soviet Dissident

If one were to dilute a Molotov cocktail enough to make its dest ructive capabilities null and void, it would be the equivalent of Kirill Serbrennikov’s Limonov: The Ballad, an ersatz biopic about infamous Soviet poet/war criminal/refugee/dissident Eduard Limonov, who died in 2020 following complications from cancer related surgery, purportedly. Based on Emanuel Carrere’s unique and incredibly researched 2011 publication, Serebrennikov (himself an infamous pariah in his native Russia who was subjected to an erroneous trial and forced to serve eighteen months under house arrest) presents a treatment which cuts so many corners it might as well have been directed for a Hollywood studio by an American who has little interest in defining the shifting world politics which assisted in crafting Limonov’s contradictory personality. In essence, Serebrennikov butchers a beautiful template provided by Carrere, and makes a film about a personality who would likely have cursed this offering before boldly proclaiming it’s not worth wiping his ass with while demanding theaters playing it be razed.

ructive capabilities null and void, it would be the equivalent of Kirill Serbrennikov’s Limonov: The Ballad, an ersatz biopic about infamous Soviet poet/war criminal/refugee/dissident Eduard Limonov, who died in 2020 following complications from cancer related surgery, purportedly. Based on Emanuel Carrere’s unique and incredibly researched 2011 publication, Serebrennikov (himself an infamous pariah in his native Russia who was subjected to an erroneous trial and forced to serve eighteen months under house arrest) presents a treatment which cuts so many corners it might as well have been directed for a Hollywood studio by an American who has little interest in defining the shifting world politics which assisted in crafting Limonov’s contradictory personality. In essence, Serebrennikov butchers a beautiful template provided by Carrere, and makes a film about a personality who would likely have cursed this offering before boldly proclaiming it’s not worth wiping his ass with while demanding theaters playing it be razed.

While Ben Whishaw performs with a lovely Russian accent as Limonov, his casting remains one of the central problems of this film, as he speaks only English, even in the film’s late 60’s sequences in Moscow. And whilst Whishaw also is aged appropriately in events spanning four decades, Serebrennikov excises all the connective tissues which bring him from Kharkov to Moscow and then New York in the 1970s, where he transitions from budding national poet to being nearly homeless and working as a butler for a millionaire while working on his first controversial novel, It’s Me, Eddie. Part of the elements mangled irreparably are the toxic relationships with women which assisted in defining his eras, including the psychotic Anna (who gets one scene before he flees to Moscow) and then his marriage to the beautiful Elena (or Tanya, in real life), a hedonistic model who eschews him to chase fame before ending up in Madrid with a Marquess. Lost is the sense of paranoia and extreme anxiety which accompanied those who fled the USSR in this period, who were made to feel as if they could never return to their homeland. Serebrennikov might assume these substantial stakes aren’t worth mentioning, but they also assisted in explaining Limonov’s perspective and how he captured the attention of both those in the West, and eventually back home.

After New York, Serebrennikov not only collapses but conveniently leaves out integral moments of Limonov’s life, including his tumultuous marriage to the transfixing Natalia Medvedeva (whose face dons the cover of the first album by The Cars). Instead, he crafts a volatile news interview with a French radio host (Sandrine Bonnaire) to exemplify Limonov’s oxymoronic nature, inflaming the guests by declaring the fall of the Berlin Wall was catastrophic for the USSR.

Next, he’s invited to speak in Moscow in 1989 for the publication of his latest novel, visits his parents, and then gets carted off to Siberia in 2000 for terroist activities. The film, once more, glosses over his establishing of the National Bolshevik Party under Yeltsin, an organization declared illegal by Putin’s regime. Serebrennikov chose to end Limonov’s journey in 2003 upon his rehearsed release from prison for Russian television. Since Carrere’s novel was published in 2011, the end subtitles mention Limonov’s support of Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, supporting the idea of Russia’s war in Ukraine. However, Serebrennikov strangely leaps over events which had already classified Limonov as a war criminal in the West (which explains why he is no longer well known here, his significant body of work no longer published in the US), which was his support of the Serbs on the frontlines of Sarajevo. Director Pawel Pawlikowski, who at one point was tipped to adapt Carrere’s novel, interviewed Limonov for his documentary Serbian Epics during this period, which includes footage of him firing a machine gun towards Sarajevo (though he would later contest what he was shooting at).

So, ultimately, there seems to be little point in Serebrennikov’s watered down Limonov, which has the audacity to include The Ballad as part of its title when it clearly avoids capturing what made Eduard Limonov extraordinary, notable, controversial, or even human. For those who haven’t had the pleasure of reading Carrere’s treatment, which includes anecdotes of his own life relating to the subject as well as excellent synopses of other Soviet literary figures and political maneuverings which all related to the worldview of Limonov, this film version merely presents a pretentious, unruly contrarian whose inflated ego and romantic ideations suggest the makings of a minor monster.

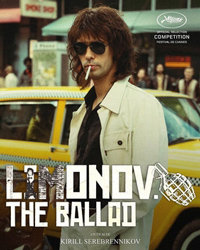

Reviewed on May 20th at the 2024 Cannes Film Festival – Competition. 138 Mins.

★★/☆☆☆☆☆