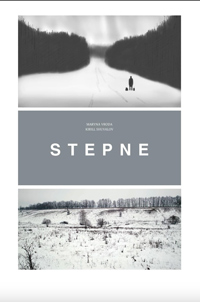

The Land That Time Forgot: Vroda Mines Eroding Memories in Speculative Debut

Thomas Wolfe meant You Can’t Go Home Again metaphorically, but such might literally be the case for the denizens of a depleted Ukrainian countryside community in Maryna Vroda’s feature debut, Stepne. The project is a long-gestating one, as Vroda has been painstakingly working on the film for over a decade, announced shortly after she won the Palme d’Or at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival for her short film Cross. Navigating a template which taps into neorealism as much as it does a docudrama, Vroda’s narrative saunters into more of a chronicling exercise of a disappearing culture than linear storytelling.

Thomas Wolfe meant You Can’t Go Home Again metaphorically, but such might literally be the case for the denizens of a depleted Ukrainian countryside community in Maryna Vroda’s feature debut, Stepne. The project is a long-gestating one, as Vroda has been painstakingly working on the film for over a decade, announced shortly after she won the Palme d’Or at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival for her short film Cross. Navigating a template which taps into neorealism as much as it does a docudrama, Vroda’s narrative saunters into more of a chronicling exercise of a disappearing culture than linear storytelling.

Anatoly (Oleksandr Maksiakov) has returned to his childhood home in the remote countryside to care for his dying mother. As her memory fails her, she sometimes doesn’t recognize him, inquiring about family or friends long gone. Along with his brother (Oleg Prymohenow), Anatoly, nicknamed Tolya, delves into old family secrets and memories, meeting up with a woman he once loved. When his mother passes, the community gathers for her funeral, resulting in a sharing of traumatic and cathartic memories amongst their own.

Vroda tends to hone in on an unyielding sense of desolation, both in the pristine wintry landscapes and the cramped interiors which range from disarrayed bedrooms to bars serving as stages to share despair. DP Andrii Lysetskyi lavishly outdoes himself with the melancholic gelidity of the remote countryside, and it isn’t surprising to see why the area’s population is dwindling. As the narrative takes a departure from Tolya, Vroda descends into documenting stories of the elders, men and women who survived wartime Ukraine, who grew up hungry and desperate. Capturing their trauma seems to be the most unique element of Stepne, as it’s difficult to differentiate confessionals from what Vroda and her screenwriter Kirill Shuvalov might have scripted.

The entrance into Stepne is a familiar angle, a distant, potentially estranged child forced to care for a dying parent. Vroda’s gaze is matter-of-fact, and there’s an austerity initially suggesting something along the lines of Austrian director Gotz Spielmann’s October-November (2013). But the region and the haunted mixture of a Russian and Ukrainian community also recalls the stark deliberations of Alexey German, particularly his 1930s set My Friend Ivan Lapshin (1985), which has more of a through line but suggests the need to examine the specificities of a certain time and place. German’s film is a period piece, but Vroda’s exercise plays like capturing echoes.

The dwindling elders, particularly the women, recall, in a much more demure sense, segments of the babushkas making doll heads in Ilya Khrzhanovsky’s impressive debut 4 (2004). With crumbling Stalin inspired artwork fading away in the woods and broken stone busts slowly overrun by foliage, Stepne evokes the words of Shelley’s Ozymandias as regards the diminished vestiges of the Soviet Union. “Nothing beside remains. Round the decay/Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare/The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

Reviewed on August 10th – 2023 Locarno Film Festival – International Competition section. 114 mins.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆