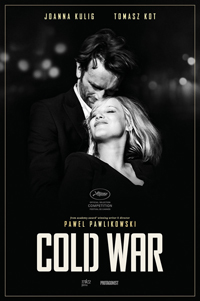

The Most Important Thing is to Love: Pawlikowski Delivers Beautifully Wrought, Chilly Amour Fou

Polish auteur Pawel Pawlikowski has had a curious trek to international acclaim. Breaking out with his 2004 the English language debut, the lesbian drama My Summer of Love, he’d return several years later with the murky and mysterious The Woman in the Fifth (read review) and make his return to Polish language cinema with 2013’s despairing drama Ida, which would win the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. Reuniting with cinematographer Lukasz Zal for his latest morbid confection, Cold War, Pawlikowski unveils another sumptuous, velvety black and white troubled relationship, this time between two lovers with artistic temperaments from different social circles, desperate to escape the crushing Communist tendencies of late 1940s Poland, rising out of the ashes of Europe’s reconstruction. With camerawork which seems to drink up the pained beauty of its two sparring yet inextricably linked leads, this is surely one of the handsomest and efficiently paced tragedies of love as an equal agent of despair as it is hope.

Polish auteur Pawel Pawlikowski has had a curious trek to international acclaim. Breaking out with his 2004 the English language debut, the lesbian drama My Summer of Love, he’d return several years later with the murky and mysterious The Woman in the Fifth (read review) and make his return to Polish language cinema with 2013’s despairing drama Ida, which would win the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. Reuniting with cinematographer Lukasz Zal for his latest morbid confection, Cold War, Pawlikowski unveils another sumptuous, velvety black and white troubled relationship, this time between two lovers with artistic temperaments from different social circles, desperate to escape the crushing Communist tendencies of late 1940s Poland, rising out of the ashes of Europe’s reconstruction. With camerawork which seems to drink up the pained beauty of its two sparring yet inextricably linked leads, this is surely one of the handsomest and efficiently paced tragedies of love as an equal agent of despair as it is hope.

In late 1940s Poland, musician Wiktor (Tomasz Kot), alongside Irena (Agat Kulesza) and Kaczmarek (Borys Szyc) tour the countryside recording the musical traditions of peasant populations, recruiting them for a stage show meant to retain the cultural heritage of their country. Upon auditioning the beautiful, enigmatic Zula (Joanna Kulig), Wiktor is instantly smitten, despite dark rumors about her troubled past. With the success of the show, their production is ordered to include propaganda within their program, which forces Irena out of the picture while Wiktor and Zula plan to defect after a performance in East Berlin. Unfortunately, their desire isn’t strong enough to overlook the consequences of such a move, which begins a cascading ripple effect between the lovers in their attempts to stay together.

Pawlikowski crafts his doomed couple in the tradition of what one might have expected from one of the many émigré auteurs populating Hollywood through the 1940s and 50s. Working with two of Poland’s most esteemed actresses, his Ida star Agata Kulesza gets a minor supporting role as a woman who quietly dismisses herself from the propaganda machine which warps her cultural project into something devious. These early sequences, graced with haunting swatches of music passed down from generations of various sources, recalls both the collection of fairy tales from the Brothers Grimm as it does the radio gimmick of Patricia Neal in Elia Kazan’s A Face in the Crowd (1957). But Joanna Kulig (who appeared in both Ida and Woman in the Fifth, as well as prominent turns in titles by Malgorzata Szumowska and Anne Fontaine) is allowed to usurp the screen as the flinty Zula, a woman from a troubled background, who after having lethally wounded her father tumbles headlong into an unstable romance with Wiktor. Resilient and formidably beautiful, she’s a blonde bombshell in the vein of a Carroll Baker but allowed a resourcefulness which instead channels either Romy Schneider or Jessica Chastain. Zal’s framing of Kulig, particularly in a Parisian set musical moment, is perhaps all the convincing we need to understand Wiktor’s obsession, and why he would flee his comfortable life in exile and ruin himself by returning to Poland. As a side note, Pawlikowski fits some fitting French tangents into these moments of exile, particularly with brief supporting stints from Cedric Kahn, and Jeanne Balibar.

While the scope of Cold War’s central relationship might recall romantic traditions of the studio era, it’s narrative is anything but nostalgic. Clipping neatly through movements, locations, and chunks of time, the film rushes us into crash landings between Zula and Wiktor, until a finale which is as cold, austere, and finite to match the apathy of their suffocating environment. Pawlikowski manages another masterful presentation of doomed humans struggling to outrun a past which will not let them go in a film as beautifully packaged as it is performed.

Reviewed on 11th at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival – Competition. 94 Minutes

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆