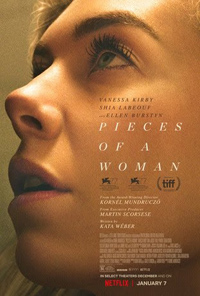

Brink of Life: Mundruczó Hunts for the Grace in Grief with English Language Debut

One of Hungary’s most prolific arthouse auteurs of the last decade makes his English language debut with the Canadian/US co-production Pieces of a Woman. At first glance, it’s a far cry from the output which defines Kornél Mundruczó’s filmography, who often explores taboo or topical subject matters girded with either sensationalism or a touch of magical realism. Reuniting with scribe Kata Weber, who penned both 2014’s White God (read review) and Jupiter’s Moon (2017), this time around he drills into a sobering character study focused on tragedy and the splintering ripple effects of grief on a contemporary Boston couple already unsteady thanks to a class divide which has defined their equality in the eyes of others.

One of Hungary’s most prolific arthouse auteurs of the last decade makes his English language debut with the Canadian/US co-production Pieces of a Woman. At first glance, it’s a far cry from the output which defines Kornél Mundruczó’s filmography, who often explores taboo or topical subject matters girded with either sensationalism or a touch of magical realism. Reuniting with scribe Kata Weber, who penned both 2014’s White God (read review) and Jupiter’s Moon (2017), this time around he drills into a sobering character study focused on tragedy and the splintering ripple effects of grief on a contemporary Boston couple already unsteady thanks to a class divide which has defined their equality in the eyes of others.

More of a throwback to classic but thorny melodramas of the New American Cinema movement in the 1970s than what might be predicted from Mundruczó (though his return to a centralized female protagonist isn’t terribly unlike his contemporary Joan of Arc medical drama Johanna, 2005), whatever the arguable detractions from its fractured narrative strands, its saving grace lies in the strength of a blistering performance form Vanessa Kirby as a woman continuously on the precipice of emotional implosion.

Martha (Kirby) and Shawn (Shia LaBeouf) are about to have their first baby, but their relationship seems to be a major point of contention for her mother Elizabeth (Ellen Burstyn), who sees the construction worker as not quite good enough for her daughter, a self-sufficient executive with ideas of her own. One of those ideas is a home birth for her baby, an experience which immediately goes to pieces when Elizabeth is unable to attend the event and Martha’s midwife can’t make it on time, necessitating the presence of her replacement, Eva (Molly Parker). While everything begins normally, Eva notices issues with the baby’s heartbeat.

Trepidation turns to despair when the baby is born only to die moments later. Fast forward several weeks and Martha and Shawn’s relationship has begun to fray dramatically, while criminal charges have been brought against the midwife. Estranged from her husband, her job, her family and herself, Martha must navigate the emotional aftermath of an unexpected tragedy and the unpredictable ripple effects which continue to define one chilly Massachusetts winter.

It’s easy to see why Pieces of a Woman might earn comparisons to Cassavetes’ output from the 1970s, featuring an ambitious narrative which wends its ungainly way to a finale which might arguably be too cathartic even as it succeeds in connoting the need to exorcise grief in order to heal and move forward. But Kirby’s performance places this more in keeping with the fraught, distressed energies of Ingmar Bergman’s women, paired with a cagey Autumn Sonata-like relationship with her crusty mother, here played by the continuously commanding Ellen Burstyn.

There’s a messiness to the explosions of emotion which sometimes feel inherently authentic, such as a Thanksgiving dinner scene in which Burstyn throws herself headlong into a monologue about her own grueling birth—but it also leads one to wonder why some of its most potent tangents are left out in the cold, which includes Shia LaBeouf as the anguished, recovering alcoholic. The wintry façade, guided by specific days used to mark the passage of time, does assist in evoking a supreme sense of discontent amongst a couple who become irreparably estranged.

LaBeouf, whose dalliances with Sarah Snook’s (a bit underutilized) cousin-in-law, who just so happens to be the prosecuting attorney, is also shunted into something of a subtext, a construction worker who has built bridges, Shawn speaks of the resonance in structures and buildings, and how certain frequencies can combine from the outside on these inside forces which sometimes result in infrastructural collapse.

Sans this metaphorical theorizing, he’s left out in the cold completely, as is the midwife played by Molly Parker (incredibly empathetic in her limited screen time), whose professional liabilities could also have used some exposition (such as how the entity employing her did nit have malpractice insurance, etc.). Martha’s associations with apples, a symbol which we eventually associate with her dead daughter, is also an interesting element in the wake of the reviled midwife Eva, the fallen woman designated as the unfortunate scapegoat.

Whatever its faults, these moments always seem to fall to the wayside whenever Kirby is onscreen in an insular but formidable portrayal of a resilient woman trying to keep her head above water. This is the type of performance which really allows Pieces of a Woman the comparison to daring, unforgettable examples of classic American cinema because we so rarely see messy, broken down portraits of women trying to determine their own thought processes while not giving a damn if they’re warm or likeable—and it’s courtesy of Kirby that this tearjerker doesn’t wallow in misery or insincerity.

Reviewed virtually on September 12th at the 2020 Toronto International Film Festival. Gala Presentations – 126 Mins

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆